The recent Cabinet reshuffle once again raised concerns about the size of the Government, and in particular its impact on the Executive’s power to control parliament through what has become known as the payroll vote. The payroll vote refers to all of those MPs and Peers who make up the Government and includes all Ministers as well as Whips and Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPS). The convention of collective responsibility means that those holding these posts do not oppose Government policy and thereby provide the Government with a large block of guaranteed support, and votes, in Parliament. The relative lack of power of the House of Lords, coupled with the difficulty of maintaining discipline in a Chamber where members are appointed for life, means that the bulk of these posts are located in the House of Commons where they can have the greatest impact. However, critics point out that by stacking the numbers in the Government’s favour in this way Parliament’s ability to provide independent scrutiny is undermined.

Government Ministers, Parliamentary Private Secretaries and indeed Whips can, and occasionally do, vote against the Government. For example, three coalition PPSs voted against the introduction of £9000 tuition fees in 2010 (two Lib-Dems and one Conservative). However, such actions are rare and the individuals concerned must resign from the Government. This in effect means setting aside any ambitions they may have for promotion, and is arguably a much more serious decision for those who have already begun to ascend the Ministerial ladder, than for those backbench MPs who may have less ambition, or at least less prospect, of obtaining Ministerial office. It may also be the case that MPs who are part of the Government are more likely to support policies which they feel part of, which may of course be why they have been brought into the government in the first place.

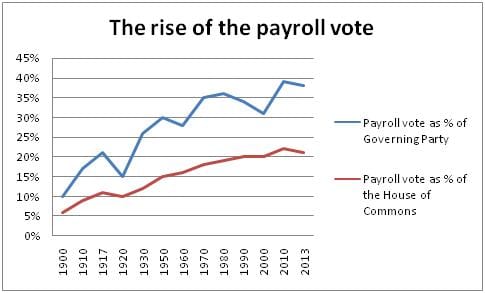

The payroll vote has grown considerably over the last century. The graph below, which is drawn from a dataset put together from The Guardian’s excellent datablog, shows how the size of the payroll vote as a percentage of the total membership of the House of Commons has grown since the start of the last century, from 6% of the House in 1900 to 21% of the current House of Commons. What is even more striking is the increase in the proportion of MPs from the governing party who have been drawn into the government. In 1900 only 6% of governing party MPs were members of the Government; 33 of these were Ministers and 9 were Parliamentary Private Secretaries. Under the current coalition government 95 MPs hold Ministerial posts, and 43 are Parliamentary Private Secretaries, with the result that 39% of coalition MPs are part of the Government. If we break that down according to the two parties in the coalition, 38% of Conservative MPs and 43% of Liberal Democrats are members of the Government.

Interestingly, there are limits on the number of paid Ministerial posts. This was set out in the Ministerial and other salaries Act 1975, which limited the number of Cabinet Ministers to 22, and the total number of Ministerial posts to 84, along with 3 law officers and 22 Whips. This effectively sought to limit the size of the Government across both Houses to 109. However, this only limits the number of paid Ministerial posts. One way in which governments have increased the size of the payroll vote has been to appoint unpaid Ministers. The last Government to have less than the statutory 109 Ministers was the Conservative government of John Major in 1992. The current government has 12 unpaid Ministerial posts. Some of these are individuals who hold two posts in the Government and so still collect a salary for one of them. Grant Shapps for example, is an unpaid for his role as Minister without Portfolio, but does pick up a salary and attend Cabinet as Chair of the Conservative Party. Similarly, Jo Johnson (Boris’s brother) is an unpaid Parliamentary Secretary in the Cabinet Office, but is also an Assistant Whip for which he receives a Whips salary.

The number of posts which are held by individuals is also interesting. There are in total 131 posts in the current Government, including Whips. However, 10 members of the Government have two posts. Although this doesn’t lead to an increase in the size of the payroll vote, indeed, quite the opposite, it does mean that if these posts were redistributed on the basis of one-member one-post, the Government could, without the need to create any new posts, bring an additional 10 individuals into the Government. Although this is unlikely to happen overnight it is one way in which the Government could relatively quietly expand the payroll vote.

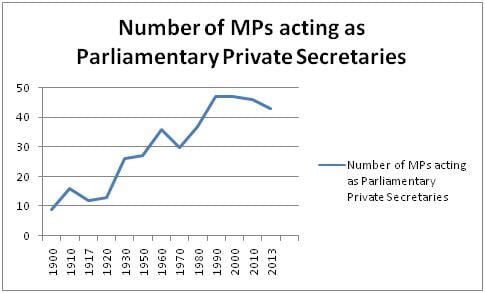

Another way which successive governments have expanded the payroll vote has been through the appointment of Parliamentary Private Secretaries. The increase in the number of these unpaid Ministerial aides has been perhaps the most significant means by which successive governments have expanded the payroll vote. Creating new PPSs is a relatively easy way of rewarding loyalty, and as long as their number does not exceed the number of Ministers, there is considerable scope for making new appointments. There are currently 43 PPSs, more than one for every two Ministerial posts in the House of Commons, although there has been a slight fall in numbers since the coalition was formed in 2010. The coalition has also been somewhat better at providing information about how many and who the PPSs are. This information, along with details of Special Political Advisors, has in the past been quite difficult to track down and as part of its pledge for greater transparency the current government has published lists. Although they have yet to publish a list following the recent reshuffle and the data presented here is based on 2012.

The continued growth in the payroll vote is, however, disappointing. A series of bodies including the Public Administration Select Committee, the Hansard Society and the Conservative Party’s own Commission to Strengthen Parliament have called for a reduction in the size of the government. Yet as The Guardian pointed out last year, this may well be the largest government ever.