Some years ago I wrote the entry on Lord Carrington for a planned encyclopaedia on NATO which never went to press. Lord Carrington’s death this week at the age of 99 provides an opportune moment to publish the entry in full here.

Carrington, Lord Peter (6th June 1919 – 9th July 2018)

Carrington, Lord Peter (6th June 1919 – 9th July 2018)

NATO Secretary-General 1984-1988. Lord Carrington was the sixth Secretary-General of NATO and the second Briton to hold the post. He took up the post on 25 June 1984, succeeding the Dutch Dr Joseph Luns, and served until June 1988.

A Conservative Peer in the British House of Lords, Carrington had held various Ministerial positions in the Conservative Governments of Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher, most notably as Secretary of State for Defence from 1970 to 1974, and as Margaret Thatcher’s first Foreign Secretary, from 1979 to 1982. Carrington’s Ministerial career came to an end in April 1982, when he resigned over the Foreign Office failure to predict the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands. A subsequent parliamentary inquiry concluded that no blame or criticism could be attached to anyone in the government for failing to predict the invasion, and cleared the way for Carrington’s return to international politics as the British candidate to succeed Luns, as Secretary-General of NATO.

Carrington’s candidature was not welcomed by everyone in the Alliance and was opposed in particular by many in the Reagan administration, most notably US Secretary of State Alexander Haig, who had clashed with Carrington in the past and openly expressed his opposition to his appointment. Carrington’s position was not helped by a speech he delivered shortly before his appointment in which he criticised the ‘megaphone diplomacy’ employed by the United States in its dealings with the Soviet Union. However, opposition from the Pentagon and the State Department was overruled by President Reagan following a phone-call from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher urging the President to support Carrington’s appointment.

Despite early misgivings, Carrington was highly regarded as Secretary-General. His recent position as Foreign Secretary, provided him with the necessary stature for the job, and meant that he was already familiar with many of the Alliance Foreign Ministers. Moreover, his experience as both a Defence and Foreign Minister meant that he had experience of both the Atlantic Council, and the Defence Planning Committee. Carrington also adopted a markedly different style from his predecessor, Luns. Whereas Luns had relied mainly on his private office, Carrington adopted a consultative style which led him to draw upon expertise from across the NATO secretariat, and endeared him to the staff in Brussels.

Like many Secretaries General Carrington spent a great deal of time seeking to reconcile the diverse national interests within the Alliance, although he was cautious about the extent of consensus that could be realistically achieved. He was fond of saying that unlike the Soviet bloc, the Western allies, ‘sing in harmony, not unison.’ Carrington’s efforts to reconcile European and American interests within the Alliance meant that despite their early concerns, Carrington enjoyed more support from the Americans than he had as British Foreign Secretary. Nevertheless, his position was not always comfortable and he once remarked that as the role of the Secretary-General was to maintain a position somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic, ‘as you would expect, I am cold, I am wet and I’m very, very lonely.’

Carrington’s tenure as Secretary-General was dominated by arms control negotiations between the superpowers, and unease among the European partners about the US development of space based defence against nuclear attack, the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI). Carrington was a strong supporter of arms control, and was instrumental in securing European support for the American position in advance of the Geneva Summit in November 1985. He also appreciated that arms control was an important ingredient in enhancing NATO’s appeal to the electorates of member nations, and in 1984, held an unprecedented meeting with the General-Secretary of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Whilst supporting arms control Carrington was also a strong advocate of building up the defensive posture of the member nations. He was more forthright than many of the NATO governments in support of SDI, and achieved unity within the alliance on the basis that: research was prudent; there should be a clear distinction between research and development; and that any further action would be a matter for negotiation with the Russians. At the same time Carrington warned that the Alliance should not be dazzled by the ‘sex appeal’ of new weapons technology and he consistently argued that the Alliance should do more to strengthen its conventional forces. He also pleased the Americans by stating that the European partners should bear most of the cost of improving conventional defence. Carrington’s championing of a greater European defence identity was also in line with plans to strengthen the European pillar of the alliance through the reactivation of the Western European Union in 1984.

Carrington also worked throughout his tenure to help resolve the difficulties between Greece and Turkey, making an early visit to Greece in July 1984 for discussions with the Greek government. In March 1987, towards the end of his tenure as Secretary-General, following an emergency meeting of the North Atlantic Council, Carrington offered to use his good offices to help resolve a dispute between Greece and Turkey when Turkish oil exploration in disputed territory in the Aegean almost led to conflict.

Since leaving the post of Secretary-General Lord Carrington continued to take an active interest in European security. From 1991 to 1992 he served as Chairman of the European Community Peace Conference on Yugoslavia, and acting as the EC’s peace envoy he made several attempts to broker a ceasefire in Yugoslavia. In 1999, Carrington was openly critical of the NATO bombing campaign against Serbia. In articles in the British media at the time of the Kosovo crisis and after, Carrington questioned the wisdom of branding the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic as a war criminal, argued that NATO air-strikes had served to harden the resolve of the Serbian leadership and caused rather than prevented the exodus of Kosovo Albanians, and consequently undermined the integrity of the Alliance.

Suggestions for further reading:

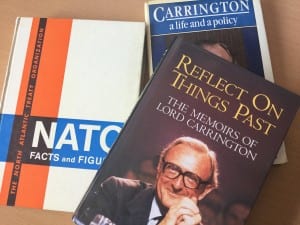

Carrington, Lord. Reflect on Things Past: The Memoirs of Lord Carrington. London: Collins, 1988.

Cosgrave, Patrick. Carrington: a life and a policy. London: Dent, 1985.