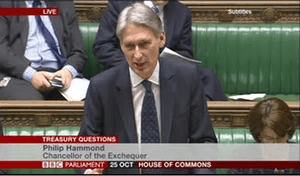

This week the Chancellor of the Exchequer will deliver his Autumn Statement. It forms part of three set-piece debates which punctuate the parliamentary year, alongside the debate on the Queen’s Speech and the Budget. It is striking that two of those, the Autumn Statement and the Budget are the responsibility of the Chancellor and that, while the Queen’s Speech and the Budget statement are familiar to many, the purpose of the Autumn Statement and its relationship to Budget are not widely understood.

This week the Chancellor of the Exchequer will deliver his Autumn Statement. It forms part of three set-piece debates which punctuate the parliamentary year, alongside the debate on the Queen’s Speech and the Budget. It is striking that two of those, the Autumn Statement and the Budget are the responsibility of the Chancellor and that, while the Queen’s Speech and the Budget statement are familiar to many, the purpose of the Autumn Statement and its relationship to Budget are not widely understood.

The media are fond of pointing out that the main difference between the Autumn statement and the Budget is that when delivering the latter the Chancellor is permitted to refresh himself with an alcoholic drink, while the Autumn statement is a more abstemious affair. However, there are other differences between the two statements which are often overlooked.

Although it takes place late in the year, as late as December in some years, contrary to some reports, the Autumn Statement actually precedes rather than follows the Budget. The parliamentary calendar begins with the State Opening of Parliament in May, the Autumn Statement takes place in November or December and is followed towards the end of the parliamentary session by the Budget statement, which usually takes place in the spring, some time around March.

The Autumn Statement and the Budget also have distinct functions. While both provide an opportunity for the Chancellor to comment on the strength of the economy, the Autumn Statement is generally used to provide details of the Government’s spending priorities and plans, while the Budget sets out the taxation measures necessary to implement those plans. To put it broadly, the Autumn Statement deals with spending, while the Budget is concerned with tax. It is perhaps not surprising then that it is the Budget, which tells people how much things are going to cost, that attracts more public attention, while the Autumn Statement can be more easily overlooked as promises yet to be fulfilled.

Indeed, the Autumn Statement can certainly appear more aspirational and is often somewhat shorter on detail. Although, like the Budget, the Autumn Statement is followed by the publication of detailed documentation, The Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the implications of this are perhaps less clear than the statements of revenue raising measures included in the Budget statement and the Red Book. Moreover, while the Autumn Statement, like the Budget, will be subject to considerable scrutiny on the floor of the House of Commons, and in the Treasury select committee, it is not subject to quite the same level of fiscal scrutiny as the Budget.

In delivery, however, the distinction between the two statements is often somewhat blurred. Chancellors will often take the opportunity of the Budget to restate spending plans already outlined in the Autumn Statement, and the Autumn Statement can have the appearance of a mini-budget. While this may have some political value, it is also understandable. There is something artificial about the notion of separating spending plans from the tax revenues needed to support them. For this reason, and following pressure both from within the Treasury, and outside bodies such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies, in 1993 the Conservative Government introduced a unified budget with a single statement, taking place in the autumn. The unified budget experiment was, however, short-lived. Following Labour’s victory in 1997, the Chancellor, Gordon Brown reintroduced the combination of an autumn statement (labelled the pre-Budget report by Labour), followed by a spring Budget and the practice has remained unchanged since. In his recently published memoirs, the former Conservative Chancellor, Kenneth Clarke, regrets the abandonment of the unified budget which he describes as a ‘very sensible approach’, although he observes with some relish that one result of this is that he is, ‘the only Chancellor of the Exchequer to have delivered a huge all-embracing Budget at this time of year.’ (Kind of Blue, p.326).

There are, however, some very good reasons why the unified Budget did not endure. As Ken Clarke suggests the production of a unified budget once a year was a monumental task. In his book The Secret Treasury, the Labour Peer, David Lipsey, argues that the Treasury ‘was never a wholehearted convert to the unified budget.’ There were, he argues, very good practical reasons for having two statements, it served to spread the, not inconsiderable, workload involved in producing a single Budget:

The separation of spending and taxes might be hard to justify in theory; in practice, it helped with the organisation of the workload. Spending could be decided in outline by Cabinet in July. Detailed negotiations would follow in August and September. The government could then announce its spending plans in November. That would clear the decks for a crescendo in work on the budget in the following March. When, however, the whole process came to a head together, at a date between the old autumn statement and the old budget, all the work had to be done at once. The Treasury never buckles, but it blanched. (The Secret Treasury, pp.122-3)

Moreover, there was, Lipsey argues, another more fundamental objection to a unified budget. Some in the Treasury were concerned that a single Budget was likely to open questions about tax to much wider debate. The Treasury recognised that its weakness in dealing with government departments in relation spending was that it was forced to consult, and that in doing so it was invariably outnumbered by other departments and that decisions would ultimately be taken in the Cabinet. In relation to tax, however, the Chancellor, has singular authority and the Treasury was keen to hold onto this. ‘Tax’, Lipsey observes, ‘is for the Chancellor alone’:

He will of course tell the Prime Minister what he plans. He will also consult individual ministers on individual taxes which affect their department; indeed they may be responsible for the detail of some of those taxes. But by tradition, he only tells the Cabinet the content of his proposals on the day he announces them to Parliament, when it is far too late for them to do other than applaud them. (The Secret Treasury, p.123)

Clarke’s memoirs also serve to illustrate the different processes involved in producing tax and spending plans. While the latter involved considerable negotiation with Cabinet colleagues, the tax side of the Budget was decided almost exclusively in the Treasury. He also notes that while spending plans involved negotiation it was often ‘fairly easy’ to gain consent, ‘because most departmental ministers were convinced that the spending total’s effects would not be borne by them’. The tightening of fiscal policy set out in tax policy was not so easy to sell.

When the Chancellor sits down after his Autumn Statement this week it is worth noting that the applause which will inevitably follow, at least from those alongside and behind him, may be far more sincere than that which will follow his Budget statement in March. When giving his Autumn Statement, the Chancellor is the friend of government departments, by the time he stand up to deliver his Budget speech in March he may well need a drink.