In electoral terms the area between the Humber and the Wash is to some extent a microcosm of England. Labour is well represented in the urban industrial constituencies in the north. To the south, the largely rural county of Lincolnshire is dominated by the Conservatives. There are pockets of support for UKIP in the less affluent coastal communities to the east and declining support for the Liberal Democrats in the south of the county. Labour does not dominate in the county town of Lincoln as it does in the nation’s capital, but it does control the city council. Lincoln is something of a bellwether constituency and is the most marginal of the greater Lincolnshire constituencies.

There are 11 parliamentary constituencies in the three counties of North Lincolnshire, North East Lincolnshire and Lincolnshire. Two of those seats, Scunthorpe and Great Grimsby, are currently held by Labour and the remainder are Conservative. Although there was no change in any of these 11 constituencies in the 2015 general election, a number of the seats were keenly fought. This was partly the result of a growth in support for UKIP in the region, and also because a number of prominent local MPs stood down in 2015, most notably in Great Grimsby and Boston & Skegness, leaving parties without an incumbent advantage.

The loss of any of these seats in 2017 would be significant for the party concerned. As the most marginal of the 11 seats, Lincoln would appear the most likely to fall, but the constituency looks safer than it has in the past and the Conservatives are confident of holding on. Labour may feel less secure in Scunthorpe and Great Grimsby.

Attitudes towards the EU may have a significant impact on voting in the region. In last year’s referendum, 59% of voters in the East Midlands voted to leave the European Union and the region contains some the most Eurosceptic constituencies in the country. UKIP have enjoyed considerable support in local government across the region and came second in five of these eleven constituencies the last time they were contested. However, despite considerable efforts UKIP have failed to turn this into electoral success at Westminster and in last month’s local elections in Lincolnshire UKIP lost all of its seats on the county council. If the collapse in the UKIP vote is mirrored in the general election, where those voters transfer their support may have a significant impact on the outcome in a number of constituencies.

This post seeks to provide an overview of the seats in the greater Lincolnshire area and review the prospects for the 2017 general election.

North Lincolnshire

Brigg and Goole

The constituency of Brigg and Goole was created in 1997 and sits on the border of North Lincolnshire and the East Riding of Yorkshire. The seat comprises the Labour voting port town of Goole and a rural hinterland around the market town of Brigg. It is by no means obvious territory for either of the main parties. The constituency is overwhelmingly white, with 95% of residents born in the UK, an estimated 66% of whom voted to leave the EU in last year’s referendum.

The seat was held by Labour from 1997 until the 2010 general election, when it was won by the Conservative, Andrew Percy on a huge swing from Labour. Percy consolidated his position in 2015 with 53% of the vote and a majority of over 11,000. Percy, a former teacher and Hull City Councillor is a prominent local figure. His national profile was enhanced by his appointment as Minister for the Northern Powerhouse in 2016.

Brigg and Goole is the kind of seat Labour need to win to return to the sunny uplands of 1997-2005 but it is unlikely to happen at this election.

Scunthorpe

Scunthorpe is more natural Labour territory. Like Brigg and Goole it was created in 1997. The town of Scunthorpe is the third largest urban area in the region after Grimsby and Lincoln. The town is dominated by the steelworks on which a large number of jobs depend. This is a precarious industry and closure was threated in 2014 when Tata Steel announced its intention to sell. The steelworks were sold to an investment company in 2016 for £1, and to the delight of many in the town reopened as British Steel Ltd.

Labour have held the seat since 1997, although their majority has fallen from over 14,000 to a little over 3,000 in 2015. The MP, Nic Dakin is the former principal of John Leggot College in Scunthorpe. He was elected in 2010 when he took over from the disgraced MP, Elliot Morley, who stood down following his imprisonment for false accounting in relation to his parliamentary expenses.

Although once a safe Labour seat, Scunthorpe is one of two Conservative target seats in the region, alongside Great Grimsby, both of which could fall if Labour have a bad night. Scunthorpe is the most delicately balanced. It would only require a 4.24% swing to the Conservatives to unseat Labour. However, Dakin is probably in a safer position than his colleague, Melanie Onn, in Great Grimsby. Having been MP since 2010 he is more well-established and may attract the gratitude of some voters for his role in brokering a deal to keep the steelworks open.

North East Lincolnshire

Great Grimsby

Grimsby is one of the oldest parliamentary constituencies in the country, having sent representatives to parliament since 1295. It is now an almost entirely urban constituency comprising the docks and historic fishing port. Although it retains a fish market most fish are now flown in from Iceland and the declining fishing industry has been a touchstone for Eurosceptic support in the town. With relatively high levels of unemployment and deprivation Grimsby epitomises the ‘left behind’ voters disillusioned with the traditional parties and strongly opposed to Britain’s membership of the EU. In last year’s referendum 71% of voters in Grimsby said that Britain should leave the EU.

The seat was held by the flamboyant Labour MP and former TV presenter, Austin Mitchell from 1977 to 2015. However, like Scunthorpe, Grimsby has seen a gradual decline in Labour support and in his last general election in 2010, Mitchell secured only a slim majority of 714. In 2015, Mitchell’s replacement, Melanie Onn, managed to increase that to over 4,540 but Great Grimsby is still high on the Conservative target list. A swing of 7% to the Conservatives would see it fall.

Onn was born and grew up in Grimsby but has only had two years to establish herself as the town’s MP. She is not from the Corbynite wing of the party and there were calls for her to be deselected when she supported a vote of no confidence in Jeremy Corbyn. She is also in the uncomfortable, but not uncommon, position of being a ‘remain’ MP in a constituency which voted overwhelmingly to leave the EU.

The seat was strongly targeted by UKIP in 2015. Their candidate, Victoria Ayling, had previously contested the seat for the Conservatives, almost wiping out Austin Mitchell’s majority in 2010. Onn’s campaign in 2015 was not helped by Mitchell’s claim that Labour could select ‘a raving, alcoholic, sex paedophile’ and still beat UKIP. Nevertheless, UKIP’s efforts in Grimsby have largely misfired. Although they secured 25% of the vote in 2015, they were beaten into third place by the Conservatives.

UKIP are once again targeting the seat, fielding the MEP and fisheries spokesman, Mike Hookem, a robust campaigner who was famously involved in a ‘scuffle’ with another UKIP MEP at the European Parliament in Strasbourg in 2016. However, the most likely scenario is a collapse in the UKIP vote which may benefit the Conservatives. The constituency could provide an interesting test for the theory that UKIP have acted as a ‘gateway drug’ for Labour voters moving to the Conservatives.

Cleethorpes

On its landward side Great Grimsby is surrounded by the constituency of Cleethorpes. Cleethorpes is, however, quite a different constituency than its neighbour. In addition to the seaside resort of Cleethorpes which is contiguous with Grimsby and the port of Immingham further up the Humber, the Cleethorpes constituency also comprises a significant Conservative-voting rural apron stretching south into Lincolnshire and west along the Humber.

The constituency was created in 1997 and was held by Labour until 2010 when it was won by the Conservative Martin Vickers. Vickers, who is a politics graduate from the University of Lincoln, had been an election agent for the Lincolnshire MP, Edward Leigh, and had unsuccessfully fought the seat in 2005.

Although Cleethorpes was targeted by both Labour and UKIP in 2015, Martin Vickers held onto the seat and increased his majority. Vickers is a vocal Eurosceptic which has helped him to see off the challenge from UKIP. His main challenge comes from Labour who beat UKIP into third place in 2015. Labour’s candidate is Peter Keith, who also fought the seat in 2015. He is the husband of the former Labour MP for the constituency, Shona McIsaac, who Vickers defeated to take the seat in 2010. Although Labour have long believed they can retake the seat, the Conservative majority of 7,893 looks pretty secure this time.

Cleethorpes is one of two seats in the region where all of the candidates in 2017 are men. The other is South Holland and the Deepings.

Lincolnshire

Gainsborough

The large rural constituency of Gainsborough in the north-west of the county of Lincolnshire has been held by the veteran Conservative MP, Edward Leigh, since 1983, but the seat has elected Conservative MPs since 1924. Aside from the small towns of Gainsborough and Market Rasen, the constituency is largely comprised of open fields and pig farms.

The Labour candidate in the seat in 2015 was David Prescott, the son of the former Deputy PM, John Prescott. This had little discernible impact on the electorate and Leigh increased his majority to over 15,000, securing 53% of the vote in 2015. This year Prescott, who was a speechwriter for Jeremy Corbyn, failed to be selected for the much safer Labour seat of Hull West and Hessle, vacated by Alan Johnson. Gainsborough is one of the seats where UKIP, who came third in 2015, are not fielding a candidate. It is a Conservative certainty.

Louth and Horncastle

To the east of Gainsborough and the south of Cleethorpes is the constituency of Louth and Horncastle. Although, like Gainsborough, this is a predominantly rural constituency it does include some pockets of deprivation on the Lincolnshire coast around Mablethorpe, which have generated support for UKIP. There is also a scattering of Labour voters, notably in the market town of Louth, where the rock star Robert Wyatt delights local Conservatives by posting ‘Vote Labour’ posters in all of the windows of his town centre home.

Louth and Horncastle is a safe Conservative seat. Prior to 2015 it was held by the father of the House, Sir Peter Tapsell, who was first elected to Parliament under Harold Macmillan in 1959. Tapsell’s successor, Victoria Atkins, is a former barrister from London. In something of a break with tradition, in what is a very traditional county, the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats are all fielding women candidates in Louth and Horncastle.

Although Louth and Horncastle has not had anywhere near the levels of immigration of the neighbouring constituency of Boston and Skegness, there was strong support (70%) for leaving the EU in the 2016 referendum and UKIP came second in the constituency in the 2015 general election. Atkins supported Britain remaining in the EU, but has supported Theresa May’s approach to Brexit since then. She increased the Conservative majority in 2015, securing over 50% of the vote. We should expect little change this time and the main interest lies in whether Labour, the Liberal Democrats or UKIP come second.

Boston and Skegness

Boston and Skegness is one of the more interesting seats in the region. Famously the most Eurosceptic constituency in the country, an estimated 75% of voters in Boston and Skegness voted to leave the EU. The constituency comprises the market town of Boston, the seaside resort of Skegness and a large expanse of arable land. Tourism and agriculture provide the bulk of jobs in the constituency. Large numbers of migrant workers have been drawn to the constituency to work in the agricultural sector. 10% of the population of Boston were born outside of the UK, mainly in the new accession states of the EU. The response to the large influx of migrant workers in a small market town has been mixed. While some have expressed concerns about the pressures placed on services such as schools and hospitals, others argue that the influx of young families has prevented the closure of schools with declining rolls and ensured the retention of maternity provision at the local hospital.

The constituency has been held by the Conservatives since it was created in 1997. The previous Conservative MP, Mark Simmonds, who stood down prior to the 2010 general election, did not endear himself to local residents by complaining about the meagre level of his parliamentary expenses. His successor, the boyish, Matt Warman, pulled off the not inconsiderable feat of supporting ‘remain’ in the EU referendum against the wishes of the majority his constituents, largely by offering a dignified and considered defence of his position and refusing to embrace the ill-informed knockabout that characterised much of the referendum campaign.

UKIP slashed 8000 votes off the Conservative majority in Boston and Skegness in 2015, but still came in second. They will try to unseat the Conservatives again in 2017 and the seat has been targeted by the UKIP leader, Paul Nuttall. However, the prospects are not good for UKIP. The party lost all of its seats on the county council in May, Nuttall has proved somewhat accident prone as party leader and, unlike UKIP’s 2015 candidate, has no connection to the constituency.

South Holland and the Deepings

Situated to the south of Boston & Skegness, the constituency of South Holland and the Deepings, is a fenland constituency centred around the market town of Spalding. It is the Conservatives 10th safest seat in the country. The current MP, the transport Minister, John Hayes, has held the seat since 1997. His majority of 18,567 is somewhat lower than the almost 22,000 votes he secured in 2010, although he did increase his share of the vote in 2015 to 59%.

This is another seat in which support for leaving the EU exceeded 70%, but Hayes unlike his neighbour in Boston and Skegness was happy to support his constituents in this. As in other seats in the region the main interest here is who comes second. UKIP came a distant second in 2015 with 22% of the vote. The Liberal Democrats were second in 2010 and Labour in 2005.

South Holland and the Deepings is one of two seats in the region where all of the candidates in 2017 are men. The other is Cleethorpes.

Grantham and Stamford

This is another safe Conservative seat in a largely rural constituency. The two towns of its name bookend the constituency. Grantham is, of course, the birthplace of Margaret Thatcher, but the town itself is largely Labour voting. This is not without its tensions. Proposals by the, Conservative dominated, county council to name the new Grantham bypass after Lady Thatcher caused a level of controversy not seen in the town since the local museum was offered a statue of the former Prime Minister.

Labour support in Grantham is, however, more than balanced by Conservative voters in Stamford in the south of the constituency, home of the Burghley horse trials. The sitting MP, Nick Boles, has a majority of almost 19,000. Boles was a close friend of David Cameron and has held a number of Ministerial posts since first being elected in 2010. He has recently received treatment for cancer, but has, thankfully, announced that he will contest the 2017 election.

The only way Labour could take this constituency is if Boles crossed the floor of the House of Commons and defected to the Labour Party, which is, of course, exactly what his predecessor Quentin Davies did in 2007.

Sleaford and North Hykeham

This will be the third time in three years that the voters of Sleaford and North Hykeham have been given the opportunity to elect their MP. Stephen Phillips who was elected as the Conservative MP for the constituency in 2015 stood down in 2016 in opposition to the government’s approach to Brexit. Phillips, who supported Britain’s exit from the EU, was nevertheless frustrated at Theresa May’s unwillingness to allow Parliament to be involved in the process. The subsequent by-election was won by the Conservative candidate, Caroline Johnson, a consultant paediatrician who campaigned, amongst other things, against the proposed overnight closure of A&E at Grantham hospital.

Johnson secured more than 50% of the vote in the by-election, albeit on a very low turnout. Her nearest rival, the UKIP candidate, Victoria Ayling (who fought in Grimsby in 2015), won 13.5% of the vote. The by-election was most notable for the woeful performance of Labour, who came second in the constituency in 2015, and fourth after UKIP and the Liberal Democrats a little over a year later.

The 2017 general election should be a little different, not least because there will be almost half the number of candidates than 2016, and turnout should be higher. Nevertheless, it is hard to see the Conservatives doing anything other than increasing their majority. Labour must do better here.

Lincoln

Finally, the city of Lincoln. This should be the most interesting of seats. Lincoln claims to be the oldest constituency in the country and is often presented as a bellwether constituency, changing hands when the government does. It was Conservative from 1979 to 1997, Labour from 1997 to 2010 and Conservatives since then. However, prior to this Lincoln was a safe Labour seat from 1945 to the mid-1970s, and for a brief period in the mid-70s was represented by the independent Lincoln Democratic Labour MP, Dick Taverne.

The city has changed considerably in recent years. The creation of large housing developments to the south of the city have hollowed out the city centre prompting boundary changes which have added more rural and Conservative voting wards from the fringes. At the same time the presence of the university has brought into the city over 10,000 students, whose vote could be decisive, if they could be persuaded to vote.

The Conservatives have a fairly slender majority of 1,443 in Lincoln. The sitting MP, Karl McCartney held the seat against expectations in 2015 and increased his majority. Further reinforcing the impression that the seat is a good indicator of the national picture. McCartney is both an affable and abrasive figure who is prone to publicly remonstrating with those he feels have slighted him. Rather like the Prime Minister he has avoided head to head debates with the other candidates, prompting some criticism in the local media. He will, however, feel confident at having seen off Labour’s challenge twice already.

In truth the seat is not perhaps as marginal as McCartney’s slender majority would suggest. Boundary changes prior to 2010 added two heavily Conservative voting wards to the south of the city which largely cancel out Labour votes in the city. The Conservatives may congratulate themselves on holding on in Lincoln, but they are perhaps making rather heavy weather of what should be a much safer seat.

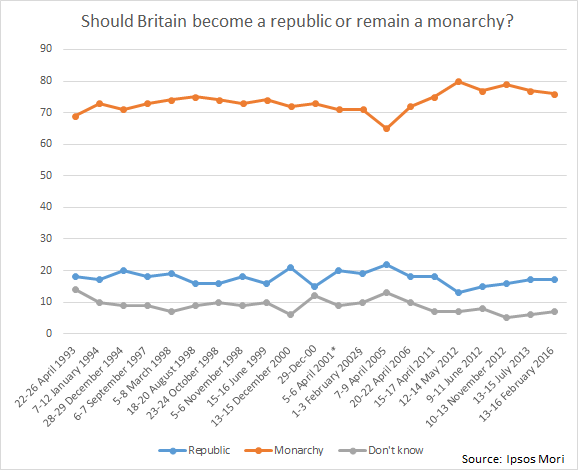

There is little doubt that the British public are strongly committed to the monarchy. Opinion polls consistently indicate that less than one in five would like Britain to become a republic while around three quarters favour Britain remaining a monarchy. Moreover, support for the monarchy remains extraordinarily stable. Even at the time of the death of Princess Diana in 1997, when polls indicated some dissatisfaction with the Palace’s response, support for Britain remaining a monarchy held steady. As shown in the graph above, there is even some evidence that support for the monarchy has increased in recent years.

There is little doubt that the British public are strongly committed to the monarchy. Opinion polls consistently indicate that less than one in five would like Britain to become a republic while around three quarters favour Britain remaining a monarchy. Moreover, support for the monarchy remains extraordinarily stable. Even at the time of the death of Princess Diana in 1997, when polls indicated some dissatisfaction with the Palace’s response, support for Britain remaining a monarchy held steady. As shown in the graph above, there is even some evidence that support for the monarchy has increased in recent years.

![DB3ZBZ-UAAEmFHG[1]](https://whorunsbritain.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2017/09/DB3ZBZ-UAAEmFHG1-300x300.jpg)