Shortly after the 2010 general election the Political and Constitutional Reform select committee of the House of Commons began an inquiry into the question of whether or not Britain should adopt a codified or written constitution. Their report, A New Magna Carta?, was published in July 2014. The report set out the arguments for and against codifying the constitution and provided a blueprint for constitutional change with three alternative approaches:

- a Constitutional Code (the status quo option): a document agreed to by Parliament, but without involving an Act of Parliament, which would set out the essential existing elements and principles of the constitution and the workings of government;

- a Constitutional Consolidation Act (the tidying-up option): this would be a consolidation of existing laws of a constitutional nature in statute, the common law and parliamentary practice, together with a codification of essential constitutional conventions;

- a Written Constitution: this would be a document of basic law by which the United Kingdom would be governed, setting out the relationship between the state and its citizens, an amendment procedure and elements of reform.

The committee also launched a public consultation seeking comments on its report, and the three proposed models for codification.

The document below comprises a submission to the consultation by students on the University of Lincoln, level 1 politics module, Who Runs Britain? The submission was debated and drafted in a series of workshops between September and December 2014.

The committee published its response to the consultation in March 2015, and this submission has now been published on the committee’s website.

Political and Constitutional Reform Committee

‘A new Magna Carta?’ consultation

Submission by students from the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lincoln

- This is a submission from first year students in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln. It is the result of a series of workshops and polling which took place as part of our first year politics module, Who Runs Britain?Students on this module are studying for degrees in politics, international relations, and social policy, and joint honours programmes combining these subjects.

- Who Runs Britain?is a core first year politics module which aims to provide an introduction to the principal actors, institutions and processes of the British political system. The topics covered in the first term are largely the same as the ten main themes outlined in the committee’s A new Magna Carta? report, beginning in September with the constitution and concluding in December with local government. This year the programme was augmented by the addition of a number of workshops designed to facilitate further discussion around the proposals included in the committee’s report. These focused on: responses to the broad question of whether Britain should adopt a codified or written constitution; examining the ten main themes identified in the committee’s report; and the process of drafting a new constitutional document.

- The information presented in this submission represents our views, the students on the Who Runs Britain? module. While tutors acted as facilitators in this process, introducing key themes through lectures and guiding discussion in seminar debates, the responses below reflect those of the students involved, and do not necessarily correspond to those of our tutors.The large number of students involved meant that it was not always possible to arrive at an agreed position in relation to all of the questions considered.Nevertheless,an attempt has been made to reflect the debate and the balance of opinion in each case.

Should Britain adopt a codified constitution?

- We were polled on the broad question of whether Britain should adopt a codified constitution early in the term. This followed a lecture on the British constitution which included an overview of the arguments for and against codifying the constitution along the lines set out in Part 1 of the committee’s report.

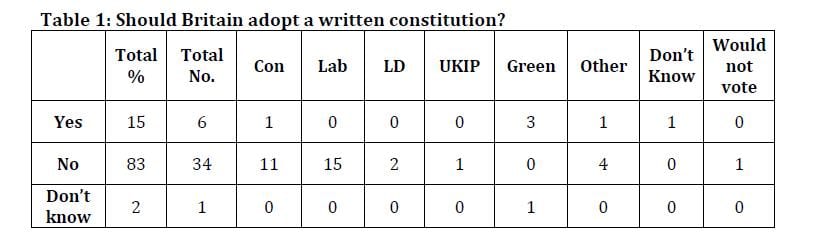

- The results of this poll were decisive with a large majority of 34 out of 41of us stating that we did not believe that Britain should adopt a written constitution. Only 6 supported the idea, while 1 was undecided, see table 1 below. The poll was combined with a poll of voting intention, which revealed that supporters of the Green Party were the only group to express significant support for a written constitution.

- In order to examine the attitudes which underpinned this poll, a

workshop was held in which we were asked to identify the single most important reason for codifying the constitution and the single most important argument against. When asked to identify the most important argument in support of codifying the constitution, the majority felt that a codified constitution would better protect rights, with responses including: ‘protects the rights of the individual’, ‘to protect and entrench citizens’ rights’, ‘the people create their rights outside and separate from government’ and ‘limits a government’s ability to make laws against minority interests’. In this group, several students also noted that further protection would come from having rights written down and accessible in a single document. After the protection of rights, the next most frequent response related to limiting the power of the government, but without any specific reference to individual rights. This was described in terms of ‘holding the government to account’, ‘providing checks and balances’ and in several cases preventing ‘elected dictatorship’. There were a range of other responses with several stating that the most important benefit would be in providing an easily accessible source or a set of guidelines for consultation on constitutional matters, such as the election of a hung parliament, while other responses included ‘it’s symbolic’, ‘securing democracy’ and ‘spreads power’.

workshop was held in which we were asked to identify the single most important reason for codifying the constitution and the single most important argument against. When asked to identify the most important argument in support of codifying the constitution, the majority felt that a codified constitution would better protect rights, with responses including: ‘protects the rights of the individual’, ‘to protect and entrench citizens’ rights’, ‘the people create their rights outside and separate from government’ and ‘limits a government’s ability to make laws against minority interests’. In this group, several students also noted that further protection would come from having rights written down and accessible in a single document. After the protection of rights, the next most frequent response related to limiting the power of the government, but without any specific reference to individual rights. This was described in terms of ‘holding the government to account’, ‘providing checks and balances’ and in several cases preventing ‘elected dictatorship’. There were a range of other responses with several stating that the most important benefit would be in providing an easily accessible source or a set of guidelines for consultation on constitutional matters, such as the election of a hung parliament, while other responses included ‘it’s symbolic’, ‘securing democracy’ and ‘spreads power’.

- When asked to identify the single most important argument against codifying the constitution responses fell largely into three categories. The majority of respondents identified the flexibility of the current arrangements as the principal argument in favour of maintaining the status quo. The next most popular response, which also related to the flexibility of the current arrangements, was the desire to not constrain future generations by the values of today, with comments such as ‘it’s fluid, governments are not held back by past governments’ and ‘democracy affects the living, not the dead, a constitution shouldn’t bind us to values of the past’. The third most popular response was the simple assertion that the current arrangements ‘work’ and that there is therefore no need for change. Finally, two respondents raised a philosophical objection to limiting the power of a democratically elected government. Interestingly, while we were clearly aware of the arguments, none of us felt that the practical difficulties involved in drafting a written constitution was the most important barrier to codifying the constitution, with several expressing the view that if it was something which had sufficient support then the practical difficulties could be overcome (see also paras. 10-14 below).

Themes for a ‘new Magna Carta’

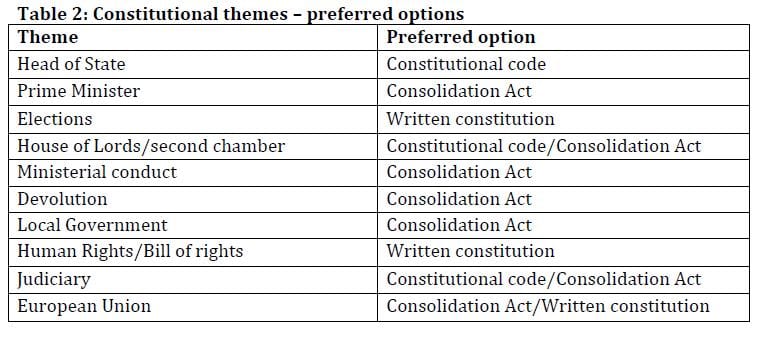

- A workshop was held in which we divided into small groups to look at the common themes identified by the committee. Groups considered how the three blueprints outlined by the committee might apply to each theme, and if possible sought to arrive at a preferred option. The results of this exercise are set out in table 2 below. Interestingly, while those taking part were overwhelmingly opposed to the adoption of a written constitution, when asked to consider which of the three options might be applied in relation to the particular themes identified by the committee,there was,nevertheless, support for codification of some aspects of the current arrangements, either through a consolidation act or a written constitution. In only one case, that of the Head of State, was a constitutional code unequivocally the preferred option.

- The following comprises a brief summary of discussion in relation to each of the themes:

i) Head of State: there was strong, although not unanimous, support for retaining the monarch as Head of State, but also a strong belief that the current powers of the Head of State should not be changed in any way. There was some support for clarifying the constitutional powers of the monarch, most notably in relation to the exercise of prerogative powers, but it was felt that in this case the necessary clarity could be encapsulated in a constitutional code.

ii) Prime Minister: in contrast, there was considerable concern at the lack of a clear constitutional role for the Prime Minister or sufficient codified limitations on the power of the Executive. The prevailing view was that the Prime Minister was, notionally at least, if not in practice, too powerful and that certain elements of Executive power should be codified, such as the existence and operation of the Cabinet, and the requirement, rather than the expectation, that the Prime Minister consult with it.

iii) Elections: in relation to elections there was support for standardising some of the current arrangements, for example, in relation to constituency sizes, and boundaries. There was a strong feeling that electoral arrangements should be lifted above political debate, and not be subject to parliamentary approval which led the group examining this issue to support the case for a written constitution.

iv) House of Lords/second chamber: there was considerable debate about the future of the House of Lords, and the group considering this issue was,perhaps unsurprisingly,unable to arrive at a preferred option. There was, however, consensus that the current House of Lords was too large and that the size of the second chamber should be fixed at a significantly smaller size than at present. While there was disagreement as to whether the second chamber should be partly or wholly appointed, there was also agreement that the remaining hereditary peers should be removed, and that if religious representation was to be a feature of the House it should encompass a range of religions.

v) Ministerial conduct: as with the office of Prime Minister, it was felt that the current statutory arrangements relating to ministerial conduct were too limited, and it was agreed,in particular,that the Ministerial Code should be enshrined in law as part of a Consolidation Act. The codification of the Ministerial Code was also seen as a means of imposing a statutory duty on the Prime Minister to ensure it is applied ‘in a sensible way’.

vi) Devolution and local government: one group looked at the issues of devolution and local government. In both cases it was observed that these issues had been dealt with in significant legislation in recent years, and there was, therefore, little need to codify what was already enshrined in law. However, in the case of local government it was felt that this was an area in which the body of legislation was so large and diverse that there was a strong case for consolidating this in a single Act, although the challenges involved in doing so should not be underestimated. Interestingly, whilst it was recognised that considerable forces had been mobilised recently in relation to the state of the Union, and also the devolution of power to local government in England, the fluidity of the situation was seen as an argument against entrenching arrangements in a written constitution, which would then be difficult to amend should opinions change.

vii) Human rights/Bill of Rights: as was indicated in paragraph 6 above, when we were asked to identify the most important reason for adopting a codified constitution, this was the one area in which there was considerable support for entrenching arrangements, and there was therefore strong support for a written constitution in this group. Moreover, it was agreed that the rights involved should include positive as well as negative rights, whereby particular rights and entitlements would be codified, rather than citizens’ rights simply being those things that parliament has not passed laws preventing them from doing, as has historically been the case, and that there should be a high threshold for changing them.

viii) The Judiciary:attitudes were divided on the role of the judiciary. Although there was strong support for the idea of parliamentary sovereignty, it was also argued that there would be some benefit in codifying the relationship between the judiciary and parliament to some extent, either through a constitutional code or a consolidation act.

ix) European Union: with regard to Britain’s relationship with the European Union, codification was seen as a more effective means of defending British sovereignty than allowing the subject to be the issue of ongoing political debate. In particular it was agreed that subsequent treaty changes should be subject to a referendum, and codification was seen as a means of entrenching this, either through a consolidation act or a written constitution.

The preparation, design and implementation of a codified constitution

10. A further workshop considered Part III of the committee’s report which relates to the preparation, design and implementation of a codified constitution. In addition to the committee’s report, we were also provided with background information on constitutional conventions, including that of the United States and more recent examples from Iceland and the Republic of Ireland.

11. Reflecting our general opposition to the idea as a whole, there was considerable skepticism about the possibility of overcoming the practical challenges involved in drafting a new written constitution for the UK. The view of one of us that drafting a written constitution for the UK, ‘would be the longest process in the history of humanity’ was not untypical. Nevertheless, we were able to identify a number of key principles which should underpin the process, if the decision was taken to adopt a written constitution.

12. How should the process be initiated? It was not felt necessary for Britain to wait for a notional ‘constitutional moment’ before embarking on a process of codification. However, we strongly feel that the process should be initiated with a national referendum to determine whether there is public support for codification. Such a referendum should not take place at the time of a general election, but should, ideally, take place in a period of relative political stability in which the issues could be properly considered without the political parties seeking to gain short–term electoral advantage.

13. Who should be involved? There was broad consensus that the public should play a central role, not just in initiating and approving a codified constitution, but also in helping to draft it. While the Icelandic and Irish models provide admirable examples in this respect, it was also accepted that there would be a need for a wide range of expert opinion to be consulted, with lawyers and academic experts, in particular, playing a central role. In contrast there was a strong feeling among many of us that politicians should play only a limited role in the process.

14. How should they be involved?There was no consensus on what the process would involve. Although the Irish and Icelandic models were viewed as good examples, it was also noted that these involved relatively small and considerably less diverse nations than the UK, and adopting a similar model for the UK might be significantly more challenging. With this in mind, there was considerable support for a written constitution to be drafted in the first instance by a panel of experts before opening it up to public consultation.This might take the form of a national consultation exercise,and there were a number of suggestions as to what form this should take including: mini-referenda on key issues, online consultation (crowdsourcing), or meetings across the country. As with initiating the process, there was consensus that a referendum should also take place at the end of the process and that this should be binding, and not subject to parliamentary ratification.

Conclusion

15. This submission represents our considered response to the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee’s various proposals for a new Magna Carta. We would like to thank the committee for the opportunity to participate in this debate. We would like to reiterate the view of the majority of this group,that Britain should not seek to adopt a new written constitution, that there are significant barriers to doing so and that in the view of some of us at least it is simply not necessary. This does not mean, however, that certain aspects of Britain’s current constitutional arrangements would not benefit from codification. We believe that there is considerable scope for improving British democracy by providing transparency and greater accountability through, for example, establishing a more clearly defined role for the Prime Minister and a statutory ministerial code, by further reform of the House of Lords and providing for greater fairness in elections. It is also the view of many of us that there are certain civil and human rights which should be enshrined in such a way as to lift them above everyday political debate, so as to make them, if not impossible, at least very difficult, to dispense with. Finally, whilst we would argue that there are significant practical barriers to the adoption of a written constitution, we do feel that the committee’s consultation on these issues and the process whereby we have debated them at the University of Lincoln, is indicative of the potential for broad and inclusive debate on important and complex issues relating to our democracy, and should be welcomed.

Fozia Ahmed, Hamid Akhavan-Hezaveh, Eden Anin-Adjei, Bennadine Antwi, Francine Baron, Jamie Bartch, Adam Bennett, Sophie Bennett, Mae Brooksbank, Joshua Charles, Aoife Costello, Philippa Cowley, Max Crouch, Tom Curley, James Dorling, Hafrica During, Thomas Eason, Samuel Emerson, Thomas Farr, Isaac Firestone, Philip Fletcher, Benjamin Gardner, Joshua Grinsell, Simona Guzmanova, Abigail Hammond, James Heap, Lauren Henderson, Coletta Ikusi, Rosemary Kennedy, Ciara Kerr, Sophie Korolewicz, Jake Lodge, Jake McCarthy, Jordan McGuffie, Benjamin Moores, Matthew Mosey, Umar Mulla, Ciaran O’Reilly, Thomas Rimmer, Sebastian Rowlands, Sebastian Puszkarek, Mat Seldon, Kayleigh Scott, Ellie Smith, Oliver Smith, Adam Stark, James Sutherland, Gerard Taggart, Ross Temple, Rio Watanabe, Charley White (students on the first year politics module, Who Runs Britain?)

Dr Andrew Defty, Reader in Politics, Dr Ben Kisby, Senior Lecturer in Politics.