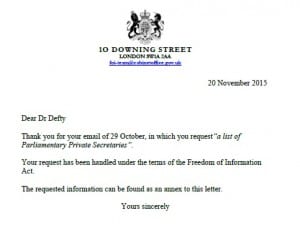

Two weeks ago I wrote a post about my frustration at being unable to find a list of Parliamentary Private Secretaries. The coalition government had published a list in 2010 but this has never been updated. On the suggestion of the House of Commons Library, who were also unable to find a list, I contacted Downing Street. The reply is opposite and the full Government PPS list is below:

Two weeks ago I wrote a post about my frustration at being unable to find a list of Parliamentary Private Secretaries. The coalition government had published a list in 2010 but this has never been updated. On the suggestion of the House of Commons Library, who were also unable to find a list, I contacted Downing Street. The reply is opposite and the full Government PPS list is below:

Cabinet:

- The Prime Minister: GAVIN WILLIAMSON

- First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer – George Osborne – CHRIS SKIDMORE

- Home Secretary – Theresa May – MICHAEL ELLIS

- Foreign Secretary – Philip Hammond – CHRIS PINCHER

- Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice – Michael Gove – ROBERT JENRICK

- Secretary of State for Defence – Michael Fallon – GRAHAM EVANS

- Secretary of State for Work and Pensions – Iain Duncan Smith – DAVID RUTLEY

- Secretary of State for Health – Jeremy Hunt – STEVE BRINE

- Leader of the Commons and Lord President of the Council – Chris Grayling – MIKE FREER

- Secretary of State for International Development – Justine Greening – ANDREW BINGHAM

- Secretary of State for Education and Minister for Women & Equalities – Nicky Morgan – ROBIN WALKER.

- Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Privy Seal – Baroness Stowell – KWASI KWARTENG

- Secretary of State for Transport – Patrick McLoughlin – STUART ANDREW

- Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills – Sajid Javid – JOHN GLEN

- Secretary of State for Northern Ireland – Theresa Villiers – REBECCA HARRIS

- Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs – Liz Truss – MARK SPENCER

- Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government – Greg Clark – HENRY SMITH

- Secretary of State for Wales – Stephen Crabb – DAVID MORRIS

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster – Oliver Letwin – ALOK SHARMA

- Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport – John Whittingdale – HEATHER WHEELER

- Secretary of State for Scotland – David Mundell – IAIN STEWART

- Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change – Amber Rudd – PAUL MAYNARD

Ministers attending Cabinet:

- Chief Secretary to the Treasury – Greg Hands – JAKE BERRY

- DWP: Minister of State – Priti Patel – ALEC SHELBROOKE

- BIS: Minister of State – Anna Soubry – MARK PAWSEY

- CO: Minister of State and Paymaster General – Matthew Hancock – GARETH JOHNSON

- Minister without Portfolio – Robert Halfon – ANDREW STEPHENSON

- Attorney General – Jeremy Wright – REHMAN CHISHTI

Ministers of State:

- Financial Secretary to the Treasury – David Gauke – CONOR BURNS

- Home Office: Minister of State – James Brokenshire – CRAIG WHITTAKER

- Home Office/MOJ: Ministers of State – John Hayes and Mike Penning – CHRIS WHITE

- FCO: Minister of State – David Lidington – JAMES MORRIS

- FCO: Minister of State – Hugo Swire – PAULINE LATHAM

- MOD: Ministers of State – Philip Dunne and Penny Mordaunt – OLIVER COLVILE

- Health: Minister of State – Alistair Burt – KAREN LUMLEY

- DfID: Ministers of State – Desmond Swayne and Grant Shapps – CHARLOTTE LESLIE

- DfE: Ministers of State – Nick Gibb and Edward Timpson – STEPHEN METCALFE

- BIS: Ministers of State – Nick Boles and Jo Johnson – ANNE MARIE MORRIS

- BIS/DCMS & DECC: Ministers of State – Ed Vaizey and Andrea Leadsom – SHERYLL MURRAY

- DEFRA: Minister of State – George Eustice – MATTHEW OFFORD

- DCLG: Ministers of State – Mark Francois and Brandon Lewis – ANDREW GRIFFITHS

The Payroll Vote

What does this mean for the payroll vote? There are 41 PPSs which is an average of around one PPS for every two Ministers. There are a total of 91 Ministers and Whips in the House of Commons which means that the payroll vote comprises 132 MPs or 40% of Conservative MPs.

Interestingly, it is not clear if this list has been made public anywhere else. I didn’t submit my request through the whatdotheyknow.com website or indeed as an FOI request, although it was treated as one. The relevant page on the gov.uk website has not been updated. The reply from Downing Street was admirably quick but with the exception of this post, it is far from clear to me that this information is any easier to find now than it was two weeks ago.