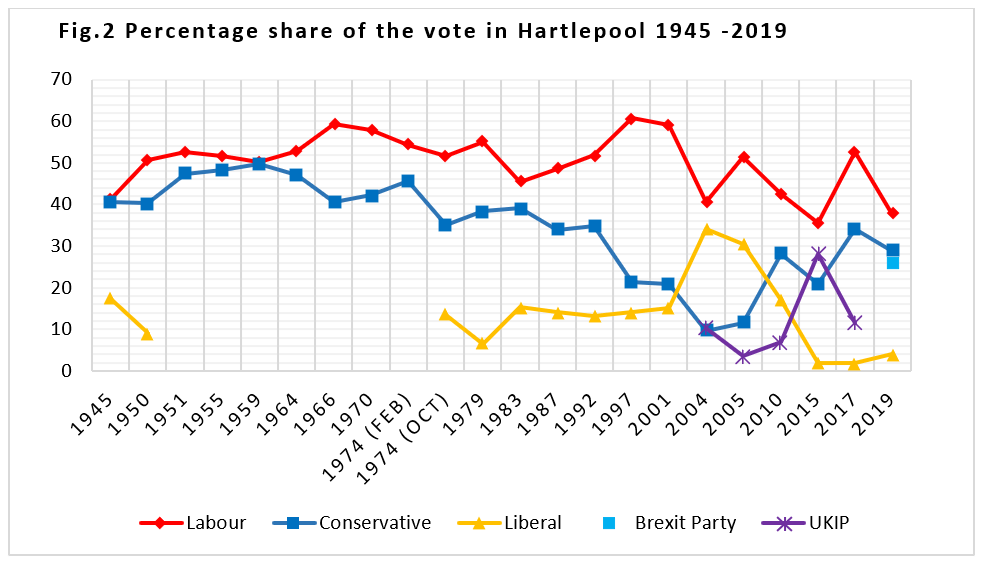

Growing up in Hartlepool in the 1970s and 80s it was often said that if you pinned a red rosette on a donkey, although not perhaps a monkey, it would be elected to Parliament. Aside from a brief period from 1959 to 1964 when the seat was held by the Conservatives, Hartlepool has been a Labour seat since 1945.

Labour won the seat once again in 2019 when a host of so-called ‘red wall’ seats fell across the North of England, including bastions of Labour support in the North-East such as Bishop Auckland, Blyth Valley and neighbouring Sedgefield. However, the resignation of the sitting Labour MP, Mike Hill, has triggered a by-election which will offer the Conservatives another opportunity to chip away at the red wall.

A by-election in Hartlepool would not normally attract much attention but political commentators, starved of by-elections for the longest period since the second world war and still digesting the remarkable gains made by the Conservatives in 2019, sense an upset may be on the cards. It is unlikely that this excitement is shared by Hartlepool voters who are being asked to elect their MP for the fourth time in six years, but are they really prepared to deliver the political bombshell that some are anticipating?

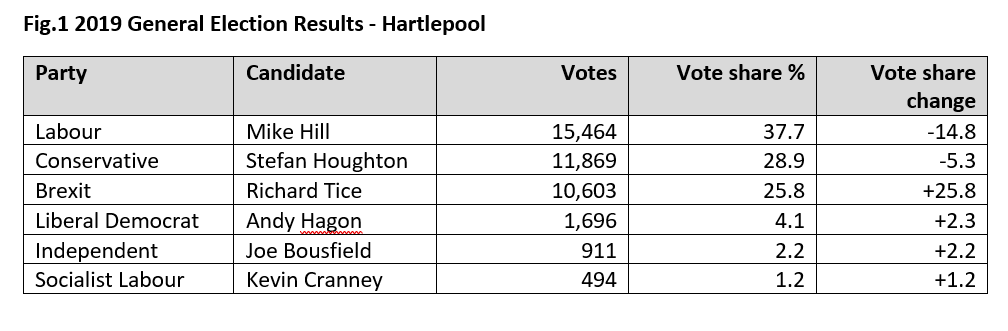

Those who think the seat may fall to the Conservatives point in particular to the results of the 2019 election (fig. 1). Labour’s share of the vote in Hartlepool fell from 53% in 2017 to 38% in 2019 and their majority was halved, bringing the Conservatives within 3,600 votes of winning the seat. Perhaps more significantly the Brexit Party, who fielded their leader Richard Tice, won more than ten thousand votes. The combined votes of the Conservatives and the Brexit Party easily exceeded those won by Labour. The not unreasonable assumption is that if just a fraction of Brexit Party voters switch to the Conservatives, then Labour will be in trouble.

Labour’s electoral dominance

It is, however, far from clear that the Conservatives can win in Hartlepool. Although Labour’s share of the vote in Hartlepool has fluctuated, in some cases quite dramatically and the gap between Labour and the Conservatives has narrowed across recent elections, (fig.2), the Conservatives would need to perform spectacularly well to overturn Labour’s hold in Hartlepool. Any incumbent going into a by-election with a 9-point lead over a governing party could normally expect to be reasonably confident of victory. Moreover, the Conservatives have rarely secured more than 30% of the vote in Hartlepool, whereas Labour routinely exceed 40%, and secured over 50% of the vote as recently as 2017. Despite a relatively poor performance in 2019 Labour still managed to rack up more than 15,000 votes, more votes than the Conservatives have attracted at any Hartlepool election since 1992. There are a lot of Labour voters in Hartlepool, if they can be persuaded to turn out and vote. The Conservatives, on the other hand, would need to win the support of new voters.

There are also grounds for thinking that Labour may be in a stronger position both locally and nationally than they were in 2019, and it is notable that while Labour’s majority was cut in 2019, they did manage to hold on when similar seats fell to the Conservatives. It is not yet clear why Mike Hill has resigned as the town’s MP, but he held on in 2019 despite the fact that he had only recently been reinstated by the Labour Party following allegations of sexual harassment. Labour will be hoping that a new candidate with a less tarnished reputation will be able to bring back Labour voters.

There are also grounds for thinking that Labour may be in a stronger position both locally and nationally than they were in 2019, and it is notable that while Labour’s majority was cut in 2019, they did manage to hold on when similar seats fell to the Conservatives. It is not yet clear why Mike Hill has resigned as the town’s MP, but he held on in 2019 despite the fact that he had only recently been reinstated by the Labour Party following allegations of sexual harassment. Labour will be hoping that a new candidate with a less tarnished reputation will be able to bring back Labour voters.

Much has also been made of Conservative victories elsewhere on Teesside in 2019 most notably in Stockton South and Darlington and the Conservative victory in the Tees Valley mayoral election in 2017. However, Hartlepool has perhaps more in common with neighbouring Middlesbrough which has returned a Labour MP at every election since it was established in 1974, than the more affluent communities of Darlington and Stockton South, both of which have elected Conservative MPs in the more recent past. It is also worth bearing in mind that the majority of voters in Hartlepool (and Middlesbrough), did not vote for the much vaunted Conservative victor in the Tees Valley mayoral election in 2017.

Moreover, insofar as the national picture will impact on this by election, although support for Labour has dipped in recent opinion polls, the gap between Labour and the Conservatives is narrower now than it was in 2019. Similarly, Keir Starmer’s approval ratings, although lower than the Prime Minister’s, are considerably higher than those of Jeremy Corbyn in 2019, particularly in the north of England.

The Brexit factor

It is also not yet clear what role Brexit might play in this by-election. Euroscepticism has been a strong political force in Hartlepool for more than ten years. The town is to some extent typical of the so-called ‘left-behind’ constituencies which voted strongly for leave in the 2016 referendum. UKIP won their first seat on the local council in 2006. The party came second in the 2015 general election in Hartlepool and second in all but one of the town’s wards in that year’s local elections. Support for leave was particularly strong in the less affluent and Labour voting parts of the town, rather than the Conservative voting wards on the more rural fringes.

It has not yet been announced whether Reform UK, the latest iteration of the Brexit Party, will be fielding a candidate in Hartlepool but their leader Richard Tice tweeted this week that the Conservatives cannot win in Hartlepool, but if they stood aside he could beat Labour. This is a bold claim from someone who came third in 2019, but Tice does have a point. Conservative hopes are built on the assumption that those who voted for the Brexit Party last time will now gravitate towards the Conservatives. However, the Brexit Party attracted more votes from disaffected Labour supporters than from the Conservatives. For Labour voters disillusioned with Westminster politics the step from Labour to the Brexit Party may be a small one compared to switching to the Conservatives. It is not unreasonable to assume that some of these may return to Labour while a sizeable proportion may stay at home.

Moreover, Brexit may not be the most significant issue in this by-election. Britain has now left the EU and a deal has been struck. Labour in particular will want to focus on other issues. The hospital in Hartlepool will be 50 years old next year. An oft-promised replacement just outside the town has never materialised. Moreover, health services in Hartlepool have been significantly eroded in recent years. There is no A&E and only limited maternity provision in Hartlepool, a town of over 90,000 people. Emergency cases and pregnant women can expect to be ferried ten miles down the road to Teesside along a congested stretch of the A19. In this context Labour’s selection of Paul Williams, a doctor who has spent lockdown working in Hartlepool hospital may well pay dividends and may even be enough to eclipse the fact that he lives in Stockton.

Electoral Volatility

Reform UK may yet have an impact on this by-election, but there may also be other beneficiaries of voters’ disillusionment with the established parties. Labour’s hold on Hartlepool’s seat at Westminster belies considerable electoral volatility in the town, which perhaps make it difficult to predict the outcome of the forthcoming by-election. The contest for Hartlepool’s seat in Parliament has not for some time been a straight fight between Labour and the Conservatives. The Liberal Democrats came second in the last by-election in the town, following Peter Mandelson’s departure in 2004, and again in the general election the following year. The party which has come closest to winning the seat from Labour is UKIP who cut Labour’s majority to just over 3000 votes in 2015. In 2019 the Brexit Party were closer to pushing the Conservatives into third place than the Conservatives were to winning the seat.

The extent of electoral volatility and the roots of Labour’s problems in Hartlepool can be more clearly illustrated by looking at second-order elections in the town. The forthcoming by-election is likely to be run in May alongside this year’s local elections when, following boundary changes, all seats on Hartlepool Borough Council will also be up for election.

The last time all seats on the council were contested at the same time was in 2012 when Labour won 23 out of 33 seats. Since then Labour’s control of the council has been eroded by the election of a succession councillors representing small special interest parties and independent candidates. Labour’s difficulties were compounded in 2019 when several Labour councillors left to join the Socialist Labour Party and Labour lost control of the council. Labour currently holds six out of 33 seats on Hartlepool Borough Council, the Conservatives hold four. There are nine parties represented on the council, including Hartlepool Independent Union (5 seats), Hartlepool People (2 seats) and Putting Seaton First (2 seats) as well as several independent councillors.

It is also worth noting that when the people of Hartlepool were given the opportunity to vote for a directly elected mayor in 2002, they elected the H’Angus the Monkey, the mascot of the local football team. The man in the monkey suit, Stuart Drummond, was re-elected under his own name, for two further terms before the people of Hartlepool voted in a referendum in 2012 to abolish the role of the mayor.

This fracturing of party politics in Hartlepool may have created space for a strong independent local candidate to have a significant impact in this by-election. Monkey suits are optional.

Prior to the 1974 general election the constituency of Hartlepool was known as The Hartlepools, reflecting the town of Hartlepool and the new town of West Hartlepool, which was established in 1847. The two were combined into a single borough in 1967. One still occasionally hears reference to the Hartlepools and the headland area of the town is widely known as Old Hartlepool.

There will be 36 seats on Hartlepool Borough Council contested at this year’s local elections.