In recent weeks questions have been raised about the involvement of the Prime Minister’s special adviser, Dominic Cummings, in decision-making in relation to the government’s response to the Coronavirus pandemic. This is not the first time that questions have been asked about the role of special advisers in the Johnson government. The Prime Minister’s decision to appoint the mercurial Cummings as a special adviser raised eyebrows and a few hackles in Westminster, when it was announced in July 2019. In August 2019 it was reported that the Chancellor, Sajid Javid was unhappy that one his special advisers had been sacked on the instructions of number 10. The Chancellor resigned in February apparently after being instructed to replace his entire team of advisers with individuals chosen by Number 10.

Javid’s resignation and the apparent desire of number 10 to control the appointment of special advisers suggests that they are viewed by ministers as an important resource and also, perhaps, as something of a status symbol. However, their role is in many respects somewhat obscure. Special advisers are temporary civil servants appointed to provide political advice to ministers. They are not appointed through the standard civil service recruitment and have a separate code of conduct. They are not bound by the duty of impartiality and objectivity which underpins the work of civil service, yet this elite group of occasionally troublesome political appointees are funded from the public purse. Moreover the annual increase in their numbers means they are becoming an increasingly costly resource.

Some element of transparency is provided through the annual special adviser data release. In recent years the government has adopted a practice of releasing these data just before the Christmas recess when it is often lost amongst other news. The 2019 release appeared on the 20th December, the day Parliament rose for the Christmas recess and only days after Parliament returned following the general election, almost guaranteeing it would pass largely unnoticed.

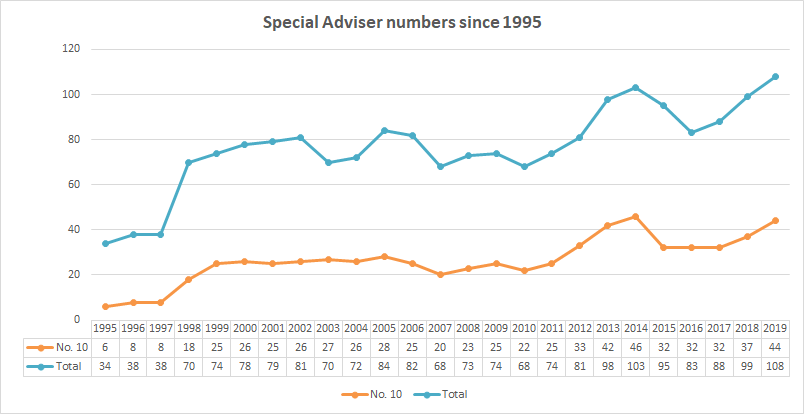

Following last year’s release, I wrote a post for Democratic Audit in which I noted that the number of special advisers has increased almost year on year since 1997 and that the upward trend has been particularly steep since 2010. This is notable not least because in opposition the Conservative Party had been critical of Labour’s use of special advisers and the 2010 Conservative manifesto had declared:

We will put a limit on the number of special advisers and protect the impartiality of the civil service.

The number of special advisers has increased again under Boris Johnson, from 99 in the final set of figures released under Theresa May, to 108 under the current government. This is only the second time that the total number of special advisers has exceeded 100, the previous occasion was under the coalition government in 2014 (see below). The numbers initialled increased considerably under the coalition, partly as a result of demands for special advisers from Ministers from both parties in the coalition. The numbers had fallen towards the end of the coalition but have risen steeply again since 2016.

This year’s increase is in part attributable to the number of special advisers located in number 10. This has increased from 37 under Theresa May to 44 under Johnson. This perhaps reflects an attempt to concentrate more power in Downing Street. The number of advisers allocated to number 10 is almost back to the peak of 46 in 2014. However, unlike under the coalition, when number 10’s special advisers were shared between David Cameron and the Deputy PM, Nick Clegg, the current batch are entirely at the Prime Minister’s disposal.

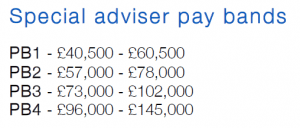

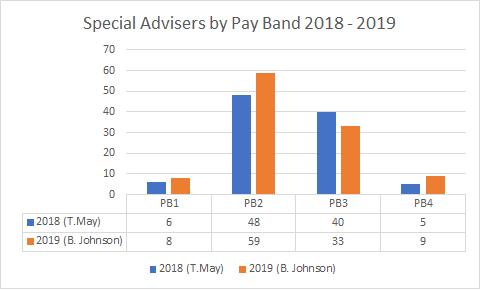

Another consequence of the increase in numbers is that there has been a significant increase in the cost of special advisers. The annual data release provides details of the total salary cost of special advisers and the four pay bands under which they are appointed (see below). Special adviser annual salaries range from £40,000 to £145,000. While individual salaries for all special advisers are not published, in keeping with other senior civil service appointments, details are provided for those whose annual salary exceeds £70,000.

The total cost of special advisers has increased considerably in the last year from £8.1 million in the 2017-18 financial year to £9.6 million in 2018-19. This included around £208,000 in severance payments, although this does not include those who left posts since Boris Johnson took over as PM including those special advisers whose sacking led to the resignation of the Chancellor. These costs are therefore likely to be significantly higher in the next financial year.

Any increase in costs will also be in no small part due to an increase in the number of the most highly paid special advisors since Johnson became PM. Under Theresa May there were five special advisers in the highest pay band, those earning over £96,000 p.a., while under Boris Johnson there are nine, including Dominic Cummings and the Downing Street Director of Communications, Lee Cain. All but one of the most highly paid special advisors are located in Number 10, with one working for the Chancellor. Seven of those in the top pay band have salaries in excess of £120,000, compared to four under Theresa May. This does not include Cummings who enjoys a relatively modest salary of between £95,000 and £99,999. Significantly, however, the total cost of special advisers in the top pay band has almost doubled under Johnson from £620,000 in 2018 to £1,149,994 in 2019.

Special advisers are now an established fixture in the machinery of the UK government. They are a significant resource which ministers clearly value and jealously guard. Although there is now considerable transparency around who these individuals are and what they earn, as recent events have shown, the precise nature or their role, powers and influence is not always so clear. If their numbers and associated costs keep on rising, questions will understandably be asked about whether this expensive resource is a worthwhile use of taxpayers’ money.

The role of special advisers was considered in more depth in an excellent Institute for Government live discussion, ‘The good the SpAd and the ugly: special advisers in government’. Available here and here.