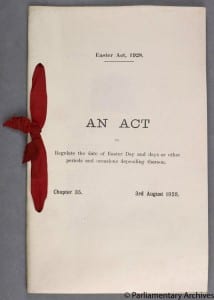

As students, schoolchildren and their teachers are acutely aware, Easter this year was ‘late’. Unlike Britain’s other major religious holiday, Christmas, the date of Easter is not fixed. Easter Sunday (Easter Day) can fall on any Sunday from March 22nd to April 25th. One result of this is that school and university terms between Christmas and Easter can vary considerably in length. Yet as parliamentary nerds are aware the date of Easter was fixed by an Act of Parliament as long ago as 1928, when Parliament passed legislation to ‘regulate the date of Easter Day and days or other periods and occasions depending thereon.’ The Easter Act, 1928, was a short Private Members’ Bill which fixed Easter day as the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April. It applies to the whole of the UK, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

If then, the date of Easter is fixed in UK law, why is it still subject to considerable fluctuation, and why this year did it fall one week later than specified in legislation?

The answer is that while the Easter Act received Royal Assent in February 1928, the central provision of the Act has never been brought into effect. In general a Bill comes into force on the day it receives Royal Assent. However, in some cases Bills include a commencement clause which sets out the timing or the circumstances in which the provisions of an Act will come into effect. In general this either specifies that an Act, or part of an Act, will come into force at a specified time or that it will be brought into effect when the government brings forward a commencement order. A commencement order is a Statutory Instrument which gives effect to the provisions of an Act of Parliament, because the Act to which they relate have already been passed by Parliament, commencement orders, are not generally subject to Parliamentary debate.

The inclusion of a commencement clause means that an Act of Parliament can remain on the statute books, but inactive, until such time as the government of the day chooses to bring it into effect. While government’s generally aim to enforce legislation within their own lifetime, if a commencement order is not introduced and the legislation is not replaced by a subsequent government, provisions can remain on the statute books, but unenforced, long after a government has left office. The Easter Act, 1928, is perhaps the most long-standing and famous example of such an Act.

The commencement clause in the Easter Act specifies that:

This Act shall commence and come into operation on such date as may be fixed by Order of His Majesty in Council, provided that, before any such Order in Council is made, a draft thereof shall be laid before both Houses of Parliament, and the Order shall not be made unless both Houses by resolution approve the draft either without modification or with modifications to which both Houses agree, but upon such approval being given the order may be made in the form in which it has been so approved: Provided further that, before making such draft order, regard shall be had to any opinion officially expressed by any Church or other Christian body. (s.2(1))

It is the final provision of this clause which has prevented the Easter Act from coming into force. Although the Bill was originally brought forward following a recommendation of a committee of the League of Nations in 1926, the international Christian community has since failed to come to agreement on the timing of Easter. The Bill itself was carefully drafted to ensure that the government was not legally bound to accept the views of the Church, but successive governments have taken it to mean that the Act would not be brought into effect until there was a general consensus on the part of the various churches of the Christian faith as to when Easter should fall.

The failure to enact the provisions of the Easter Act has been the subject of occasional parliamentary interest since 1928. This has generally taken the form of repeated questions by a succession of, perhaps slightly obsessive, MPs who have variously argued that fixing the date of Easter would benefit Britain’s businesses, regularise school terms or allow workers to enjoy more spring sunshine. The most recent example of this is the Conservative MP, Greg Knight, who for the last seven years, has heralded the imminent arrival of Easter by asking the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, when the Easter Act would be brought into force. Incidentally, Mr Knight has also been a vocal advocate of retaining British summer time throughout the winter.

There have also been a number of unsuccessful attempts to bring forward Private Members’ Bills to force the commencement of the 1928 Act. While these have allowed for more lengthy, and occasionally esoteric, debate on, amongst other things, the ecclesiastic and lunar explanations for the timing of Easter, they have been no more effective in persuading the government to give effect to the Act. In 1951 the Labour MP, Sir Richard Acland sought to bring forward a Bill to amend section 2 of the Act to bring forward its provisions without the need to consider the opinions of the Church. More recently, in 1999 the Conservative hereditary peer, Earl of Dartmouth, sought to bring forward the Easter Act 1928 (Commencement) Bill, which would force the government to give effect to the 1928 legislation. Earl Dartmouth argued that ‘the floating date for Easter has its real basis in neither religion nor science but in what might be termed happenstance or even accident’. He argued that ‘businesses, retailers and all manufacturers would all like to know the date of Easter well in advance’ and that ‘such a fixed date would also make life easier for parents, teachers and all would-be tourists and travellers.’

Despite several decades of parliamentary questions on the subject, and several Private Members’ Bills there is little evidence that there is any prospect of a change to Easter’s floating date. The responses of successive governments to questions on the Easter Act have differed little from that offered by the Home Secretary, Samuel Hoare, in 1939:

I am afraid it is impossible to bring the Easter Act into force until there is agreement amongst the religious communities, and there appears to be no immediate prospect of such agreement.

Despite falling church numbers, and a growth in the observance of other religious faiths, the inability of successive governments to do something as simple as fix the date of a public holiday is indicative of the continued impact of religion on British life. The continued failure to give effect to the provisions of the Easter Act also illustrates the difficulty of legislating in an area defined by global forces beyond the government’s control. It is not the will of the British people, or the vagaries of party politics, which have frustrated application of this decades old legislation, but a seemingly interminable debate within the global Christian community. The Easter Act is also a stark illustration of the importance of commencement clauses. The Easter Act may be an extreme example, but it does provide a warning that getting provisions onto the statute books does not guarantee that the proposed changes will come about. In scrutinising legislation it is worth noting that commencement clauses matter, and those wishing to bring about real legislative change should take care to examine them in detail.