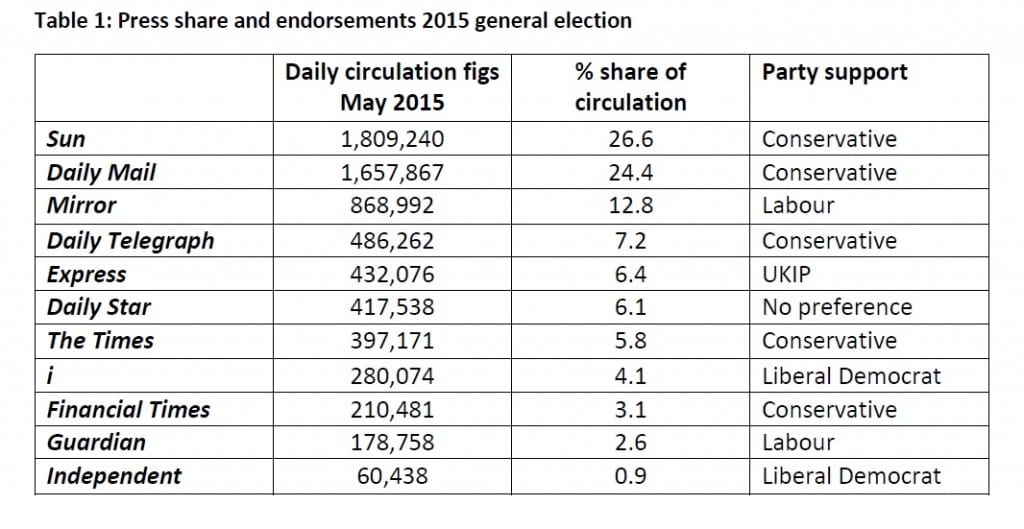

At the 2015 general election five out of eleven national daily newspapers supported the Conservative Party. Only two supported Labour, The Mirror and The Guardian, although this was an improvement on 2010 when The Guardian, somewhat bizarrely, encouraged its readers to vote Liberal Democrat. Liberal Democrat support this time was confined to The Independent and its tabloid partner i, although The Independent somewhat complicated matters by advocating a continuation of the coalition government, something which would not, of course, appear on the ballot paper. UKIP gained the support of the Express which had supported the Conservatives in 2010. In terms of circulation, Conservative press share in 2015 was 71% compared to 15% for Labour and 5% for the Liberal Democrats. Just two newspapers, The Sun and The Daily Mail, delivered more than 50% press share to the Conservatives.

At the 2015 general election five out of eleven national daily newspapers supported the Conservative Party. Only two supported Labour, The Mirror and The Guardian, although this was an improvement on 2010 when The Guardian, somewhat bizarrely, encouraged its readers to vote Liberal Democrat. Liberal Democrat support this time was confined to The Independent and its tabloid partner i, although The Independent somewhat complicated matters by advocating a continuation of the coalition government, something which would not, of course, appear on the ballot paper. UKIP gained the support of the Express which had supported the Conservatives in 2010. In terms of circulation, Conservative press share in 2015 was 71% compared to 15% for Labour and 5% for the Liberal Democrats. Just two newspapers, The Sun and The Daily Mail, delivered more than 50% press share to the Conservatives.

The overwhelming Conservative domination of the press would seem to reinforce the argument that press support is central to electoral fortunes. Moreover, as Wilks-Heeg, Blick and Crone have shown across recent elections press affiliation appears to be swinging more dramatically between the parties and in line with electoral outcomes. As they show for most of the post-war years press share between the main parties remained stable with the Conservatives having around 50-55%, while Labour sat on 38-44%. This changed in 1979 when for four successive general elections Conservative press share exceeded 64% (over 70% from 1979-1987), this was followed by three successive general elections in which Labour’s press share did not drop below 58%. In 2010, press affiliation shifted back to the Conservatives who have retained 71% press share for the last two general elections.

The parties clearly think press support is important and the fact that there are now clear winners and losers in this competition almost certainly has an impact on party morale during election campaigns. However, it is, of course, hard to know exactly what influence if any, the press has on voting behaviour and in particular whether this is evidence of newspapers following public opinion in order to hang to readers or of the press influencing the voting behaviour of their readers.

There are a number of reasons to doubt that the press has a decisive influence on voting behaviour. There is clearly no direct correlation between press share and share of the vote. Historically Conservative press share has exceeded their share of the vote, while Labour’s press share, particularly in recent years, has tended to fall below theirs. Moreover, since the 1980s the Liberal Democrats have secured large shares of the vote with very little or no press support. Most notably in 1997, the Liberal Democrats secured 17% of the vote and 46 MPs despite not having the support of a single national daily newspaper. In 2015, Conservative press share was almost double their share of the vote, while for Labour, the Liberal Democrats and UKIP their press share was roughly half of their vote share.

It is apparent then that, while Britain has a highly partisan press, the newspaper one reads does not necessarily define one’s political affiliation. There is clearly some link, polling data from 2015 clearly indicates that the majority of Guardian and Mirror readers vote Labour while the overwhelming majority of Telegraph and Daily Mail readers vote Conservative. However, a small proportion of Guardian readers vote Conservative(6%) while a similarly small proportion of Telegraph readers (9%) voters Conservative. In the course of our research on MPs’ attitudes to welfare, it was clear that a large proportion of Labour MPs are avid readers of The Daily Mail, and not always to find out what the opposition thinks.

Moreover, in order for a newspaper to influence its readership it is necessary for the readership to know what its political affiliation is and also for them to vote. While considerable attention and effort from the parties has focused on securing the support of The Sun, research on the 1997 general election suggested that any shift in allegiance on the part of the newspaper and its readers was largely offset by the large proportion of Sun readers who simply do not vote, as many as one in four. Moreover, despite well-publicised shifts in allegiance there is evidence to suggest that a large proportion of Sun readers are unaware of the paper’s political allegiances. Polling by Lord Ashcroft albeit in 2012, long before the general election, indicated that less than half of Sun readers correctly identified which party their newspaper supported. Sun readers were more likely to say they did not know which party the newspaper supported and more than twice as likely to wrongly identify its politics than readers of other national daily newspapers.

What is also striking about table 1 above is that the national daily newspaper readership in the UK is tiny. The circulation of daily newspapers in the UK is in, seemingly terminal, decline. National daily newspapers lost around half a million readers (7.6%) in the year prior to the general election. Out of a total electorate in May 2015 of around 45 million, the total daily circulation of national newspapers in the UK was around 7 million, one in six voters. The circulation of some national newspapers is so small one wonders how they stay in business. The daily circulation of The Independent, at 60,400 is not much higher than for some of the larger regional newspapers in the UK. It is tempting to conclude that the entire readership of The Guardian is made up of the 190,000+ academics in UK universities. It is hard to attribute significant political influence to newspapers which are read by such a small proportion of the voting public.

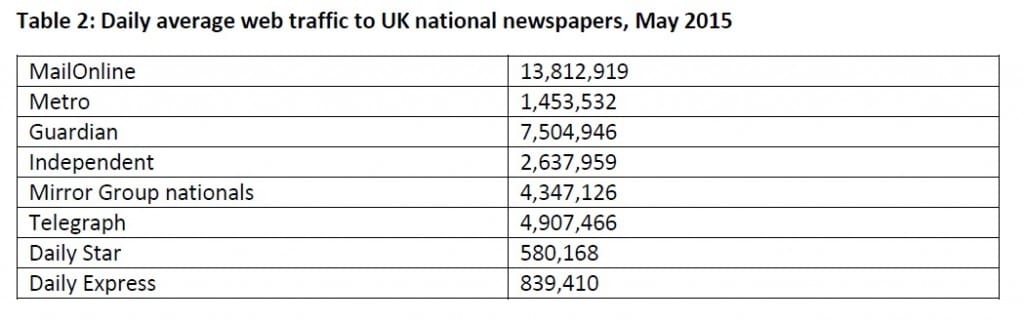

However, while print sales are in decline this has been at least partly offset by the online presence of Britain’s daily newspapers which has grown significantly in recent years. Assessing the impact of Britain’s online media is even more difficult than trying to determine the impact of the print media. While the print circulation of national dailies is almost exclusively within the UK, online editions can be accessed from anywhere in the world. The situation is complicated by the fact that the Audit Bureau of Circulation with provides figures for web traffic does not provide figures for those newspapers which operate behind a paywall. Moreover, the nature of online browsing may mean that readers are more likely to be led directly to the story they are interested in without being distracted by extraneous stuff, like politics. It is noticeable that traffic to UK national newspapers fell in the month leading up to the general election. It is also the case that while one is likely to buy only one copy of a newspaper one might visit its website on several occasions, and from several different computers, in any one day.

Nevertheless, the daily average web traffic for UK national newspapers (table 2) is dramatically higher than their print circulation. If taken together they provide a notional figure which is much closer to the total UK electorate, although this is clearly methodologically problematic for the reasons set out above. Moreover, while the Mail Online is the dominant web presence, newspapers which have a relatively low print circulation, notably The Guardian and The Independent, have a significant online reach. In contrast The Sun is a relatively small online player, it has operated behind a paywall since 2013 and only recently (since the general election) began to make more of its content available for free. The traffic figures for The Sun are, nevertheless, less than half those of The Independent and a quarter those of the Mirror.

Britain has a highly partisan press and in recent years political parties have spent a great deal of energy and money chasing the endorsement of various sections of the print media. However, there are significant questions about whether this has a significant or indeed any impact on electoral fortunes. On the basis of the 2015 general election while it may be too soon to say that parties can relax about the political endorsement of the press, they can perhaps afford to be less obsessed and think more broadly about where voters are getting their political information.