As part of it’s consultation on codifying the British constitution, which is being conducted under the banner A New Magna Carta, the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee of the House of Commons is running a public competition to find who can write the best preamble for a modern written constitution for the UK.

As part of it’s consultation on codifying the British constitution, which is being conducted under the banner A New Magna Carta, the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee of the House of Commons is running a public competition to find who can write the best preamble for a modern written constitution for the UK.

A constitutional preamble is a short introductory statement. However, while most states in the world have written constitutions the form and composition of constitutional preambles varies considerably. Indeed, some constitutions have no preamble at all, most notably those of the Scandinavian states. Those that do vary dramatically in length, the preamble to the Constitution of the United States of America, for example, is only 52 words long, while the Iranian constitution, in translation at least, has a preamble of more than 3000 words which includes an essay on the history of the establishment of the Islamic Republic. As this suggests there is also considerable variation in the content of constitutional preambles. Preambles often seek to establish the source of authority for the constitution, with some reference to the people, a monarch or a deity. They may also aim to summarise the main legal principles of the constitution or more often encapsulate the values which underpin it. In some cases this might involve a history or explanation of the formation of the constitution or the state itself, while in others it may be little more than a set of aspirations. While this can lead to high-flown rhetoric, constitutional preambles also often include rather banal details such as a list of the territories to which the constitution applies.

Perhaps the most famous constitutional preamble is that of the Constitution of the United States of America. This states that:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Considerable attention has focused on the precise meaning of this short preamble, and also the power which it embodies, to the extent that in 1905 the US Supreme Court ruled that the preamble is not a source of state power or individual rights, but that the legal power lies in the articles and amendments which follow it. Nevertheless, the US preamble has considerable symbolic force. There is a strong sense of common endeavour and of unity in this preamble, although the appeal for perfection is qualified somewhat with reference to a ‘more perfect Union’, rather than one which is absolutely perfect. The appeal to justice, tranquility, welfare and liberty may seem to suggest the state has considerable responsibility for its citizens, but is often interpreted at as refering to the individual’s right to freedom from state intervetion, enshrining negative rather than positive rights.

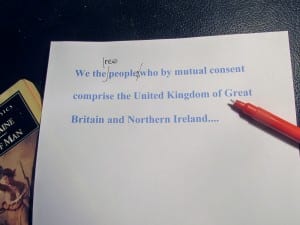

The first three words, ‘We the people…’ are perhaps the most significant, and well known words of the entire US constitution. The preamble clearly establishes that power will reside with the people. This was deliberately designed to distinguish the US from the old world from which it was seeking break free, in which power lay with the monarch. The US preamble, and indeed the constitution which follows it, is about making a clean break with the past and establishing a new and better way of doing things in which people had rights and the power of government should be restrained.

We can also see this in the preambles to the constitutions of other states which have undergone fundamental or revolutionary change. The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany for example was written in the aftermath of the Second World War when Germany was occupied by the Allies. As with the preamble to the US Constitution it invests considerable power in the people. It also establishes clear commitments to world peace, freedom and self-determination.

Conscious of their responsibility before God and man, Inspired by the determination to promote world peace as an equal partner in a united Europe, the German people, in the exercise of their constituent power, have adopted this Basic Law. Germans in the Länder of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Berlin, Brandenburg, Bremen, Hamburg, Hesse, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig-Holstein and Thuringia have achieved the unity and freedom of Germany in free self-determination. This Basic Law thus applies to the entire German people.

For quite a different constitutional preamble, see the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 which was passed by the Westminster Parliament to give Australia something which the UK still does not have, a constitutional document. In contrast to those examples cited above, the people hardly feature at all in the Australian Constitution Act, but the monarch looms large:

Whereas the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania, humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God, have agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and under the Constitution hereby established:

And whereas it is expedient to provide for the admission into the Commonwealth of other Australasian Colonies and possessions of the Queen:

Be it therefore enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows :-

Both the Australian and German preambles also include some indication of the territories to which the constitution will apply.

Another modern constitutional preamble which seeks to deal with a difficult past, and establish a new more positive vision of the future is the remarkable preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa which was drafted in 1996:

We, the people of South Africa, Recognise the injustices of our past; Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

We therefore, through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to- heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights; Lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law; Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person; and Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations. May God protect our people.

Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso.

One notable feature of the US constitutional preamble is that there is no place for God. Many other constitutions, however, do assert or appeal to the authority of some higher being. The (very long) preamble to the Constitution of the Islamic State of Iran begins, ‘The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran advances the cultural, social, political, and economic institutions of Iranian society based on Islamic principles and norms, which represent an honest aspiration of the Islamic Ummah.’ Similarly, the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland begins with an appeal to ‘the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred. We, the people of Éire, humbly acknowledging all our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial.’ The constitution of Greece invokes the ‘ name of the Holy and Consubtantial and Indivisible Trinity’.

The ommission of God from the preamble of the US constitution is deliberate and is sustained throughout the rest of the document. Other states are even more explicit in excluding God. The preamble to the Constitution of India, for example, begins by asserting that ‘We the people of India, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a sovereign socialist secular democratic republic…’ Of course, the exclusion of God from a state’s constitution does not mean that religion may not play a central the state. There are very good reasons for excluding religion from the constitution of a country in which several different religions have significant numbers of followers.

There are then many things to consider when drafting a preamble for a notional UK constitution: the status of the people, the monarch, religion; the description of the constituent parts of the United Kingdom; the inclusion of some historical element, and/or a vision of the future; the inclusion, or not, of some reference to the machinery of government, or the sovereignty of parliament; the establishment of national values or aspirations; or the inclusion of fundamental rights or expectations. While constitutions tend to limit themselvs to the state to which they apply, there may now also be a case for acknowledging, perhaps particularly in the preamble, a state’s wider responsibilities to for example, respect international law, the sovereignty of other states, or protect the environment.

This is an interesting intellectual exercise but the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee’s competition to write a preamble for a modern written constitution offers a real opportunity to influence a debate which is gaining traction. Entries which should be no longer than 350 words can be submitted through the Committee’s website. The closing date is 1 January 2015. Entries will be posted on the PCRC website, where a number can already be read. A prize will be awarded to the best entry under three categories the best entry by a member of the public, a young person under the age of 18, and by a journalist. So get writing!

There are number of excellent websites and databases comparing constitutions including: