The rise in judicial review in recent years has brought the judiciary into conflict with governments of either persuasion. In the main this has involved judicial decisions on whether public bodies (the government, ministers and local authorities) have exceeded their powers by carrying out actions which the law did not give them the power to do. There have been a diverse range of cases, from the sentencing powers of the Home Secretary to the decision about where the remains of King Richard III should be interred. There has been a rash of recent cases in which individuals and groups have taken local authorities to court to challenge their decisions to impose cuts on things like library services and social care. Politicians, of either political hue, have perhaps not surprisingly been frustrated by what they see as judges seeking to overturn the democratic will of parliament. In this article in The Daily Telegraph from 2005, the former Conservative Home Secretary, Michael Howard, criticised the Labour Government for introducing the Human Rights Act, effectively enhancing the powers of the judiciary at the expense of parliament. Labour Ministers too, came to regret this apparent enhancement of judicial power. The former Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett has been a particularly vocal critic of judicial activism, as is exemplified in the following extract from his diaries:

Judicial review is a modern invention. It has been substantially in being from the early 1980s, and although it was designed to prevent administrative abuse – where there was no parliamentary authority and where bureaucrats were exercising undue power – it had rapidly become and entirely new arm of our constitution, operated by judges, through judges, and without any redress or accountability to Parliament. In fact unlike statute law, there is a presumption that this is both outside the remit of parliament and a check on Parliament. I accept, as all democrats do, that it is the right of the independent judiciary to question the implementation of laws where those laws are not in line with the policy intent or the legislative measures passed by Parliament, but not that the intent and policy objective of Parliament can be overturned as though we have a written constitution, and a Supreme Court as a separate arm of that Constitution, as in the United States – not least because in the United States the Supreme Court is appointed through the Presidency and is scrutinised by the legislature. In Britain judicial review is all about the rights of the individual over the rights of society. David Blunkett, The Blunkett Tapes: My Life in the Bear Pit, London: bloomsbury.

The current government has been strongly critical of what it sees as the growth in time-wasting appeals against various aspects of government policy. In a recent article in The Daily Mail, the Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, bemoaned the use of judicial review by campaign groups as a legal delaying tactic designed to stop government development project ‘often delaying an innovation that would bring economic benefits and jobs.’ Such groups, Grayling bizarrely claimed, are often led by left-wing campaigners who flooded the charitable sector in an exodus from Westminister following the last general election, and are now busy exploiting the legal system in order to ‘articulate a left-wing vision which is neither affordable nor deliverable.’

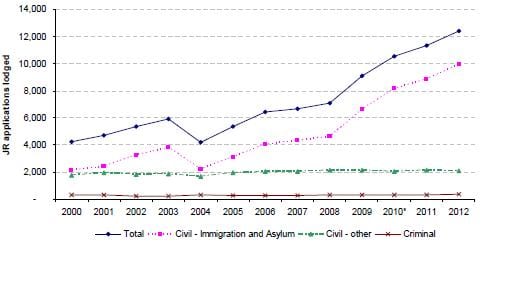

However, while Grayling, and the Prime Minister, have both attacked judicial review as a break on large scale commercial projects, as the BBC’s legal correspondent Clive Coleman, points out figures for judicial review indicate that the majority of cases of judicial review relate to immigration and asylum appeals and that the increase in cases involving commercial planning and building has been negligible. This is clear in the graph above, which is drawn from the Ministry of Justice’s own figures and shows the number of judicial reviews lodged since 2007. It indicates a clear rise in the total number of applications, but this is mirrored very closely by the rise in appeals against immigration and asylum decisions. Reviews in relation to planning decisions, which are included in the ‘civil – other’ category have seen little if any rise since 2007. Moreover, the graph is taken from a Ministry of Justice statistical notice issued last month which revised down the figures on judicial review in the ‘civil – other’ category, which had shown a slight rise in the previous statistical notice issued in June. There is then very little evidence for a rise in judicial reviews against development projects since the 2010 general election. There remain questions both about the capacity of the legal system to handle the overall rise in cases, and perhaps more significantly about the growing propensity of politicians to question the power of the judiciary, but a more accurate appraisal of the problem would certainly be more helpful.