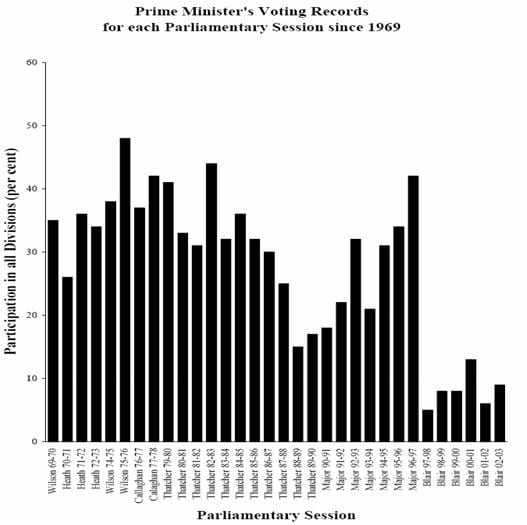

In a series of papers for the right-wing Centre for Policy Studies the Conservative MP, Andrew Tyrie, highlighted the problem of Prime Ministerial neglect of Parliament under Tony Blair, characterising Parliament as, Mr Blair’s Poodle. The data presented by Tyrie included Prime Ministers’ voting records (see Tyrie’s graph right). This showed that Tony Blair had the lowest voting record of any postwar Prime Minister. In his first parliament from 1997-2001 Blair participated in only 8.6% of votes in parliament, and the following parliament from 2001-2005 he voted in only 7.5% of votes. Blair also holds the record for the lowest level of participation in a single parliamentary session (a parliamentary year) for 1997-98 when he took part in only 5% of votes. In contrast Blair’s predecessor John Major consistently participated in upwards of 30% of votes in each session for which he was PM, and in his final session as PM participated in well over 40% of parliamentary votes. Tyrie, who it should be noted does have a particular party political view, observed that:

In a series of papers for the right-wing Centre for Policy Studies the Conservative MP, Andrew Tyrie, highlighted the problem of Prime Ministerial neglect of Parliament under Tony Blair, characterising Parliament as, Mr Blair’s Poodle. The data presented by Tyrie included Prime Ministers’ voting records (see Tyrie’s graph right). This showed that Tony Blair had the lowest voting record of any postwar Prime Minister. In his first parliament from 1997-2001 Blair participated in only 8.6% of votes in parliament, and the following parliament from 2001-2005 he voted in only 7.5% of votes. Blair also holds the record for the lowest level of participation in a single parliamentary session (a parliamentary year) for 1997-98 when he took part in only 5% of votes. In contrast Blair’s predecessor John Major consistently participated in upwards of 30% of votes in each session for which he was PM, and in his final session as PM participated in well over 40% of parliamentary votes. Tyrie, who it should be noted does have a particular party political view, observed that:

Tony Blair dominates the executive more and bothers with Parliament less than any other Prime Minister in modern times… What distinguishes Tony Blair… is [his] neglect of, even disdain for Parliament. The decline of Prime Ministers’ activity in Parliament is of long standing but it has sharply accelerated since 1997. Except to make statements and his annual Prime Minister’s Questions, Tony Blair rarely visits the Commons. In the first two full Parliamentary sessions, the Prime Minister led his Government in debate on the floor of the Commons on only three occasions – less often than any Prime Minister in recent history. He also rarely appeared in the House to vote, giving MPs, particularly those on his own side, little opportunity to buttonhole him informally. His voting record is inferior to that of any Prime Minister since the War. Tony Blair’s contact with the Commons is little more than tokenism. (Andrew Tyrie (2000), Mr Blair’s Poodle: An agenda for reviving the House of Commons, Centre for Policy Studies).

While Tyrie makes a powerful argument, and the data is clear, another explanation for the sharp decline in Prime Minsterial participation particularly from Major to Blair is that Major had such a small majority, particularly by his final session, that he needed every vote he could get (including his own) in order not to be defeated in parliament. In contrast Blair had large majorities of 179 in 1997 and 167 in 2001 and a sizeable majority of 66 in 2005. In short he simply did not need to turn up. If we compare Blair with Thatcher after 1983, when she had a majory of 144, rather than Major, Blair’s level of participation is lower but comparable.

There are also, other factors to bear in mind. The long term trend suggests that Prime Ministerial participation has been in decline since the war. This may be the result of a growth in Prime Minister’s duties, in particular their overseas responsibilities. While overseas trips are now much easier than in an earlier age when the PM could be away for several weeks at an overseas summit, partly as a result, there are now many more of such meetings. In an average year the British Prime Minister can expect, at least, to attend: the annual G8 summit; up to four European Council meetings; a trip to the UN; a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting; and several meetings with other heads of state most notably the US President. If one adds to this trips related to the launch of military action which dominated the terms of Blair and to some extent Cameron, then there are many occasions when the PM is simply not around to vote. We get a clear indication of the impact of responsibility on parliamentary voting if we look at David Cameron’s voting record. Between 2001 and 2005 when Cameron was a backbench MP he voted in 67% of votes. From 2005 to the 2010 general election, the parliament in which he was Leader of the Opposition, he voted in 25% of votes and since becoming Prime Minister he has participated in around 17% of votes in parliament.

It is also possible to argue that, while Blair attended Parliament less, he did introduce a number of reforms that made the Prime Minister more accountable to Parliament. He changed Prime Minister’s Questions from two fifteen minute sessions a week, to its current format of one half-hourly session a week. While some have argued that this meant he only needed to come to Parliament once a week instead of twice, it has also allowed for a more sustained questioning. Blair also changed the convention whereby Prime Ministers did not appear before parliamentary select committees, by agreeing to appear annually before the Liaison Committee, which is comprised of the Chairs of all the select committees. These sessions which often last over two hours, mark a significant opportunity to hold the Prime Minister to account. Blair’s performance before the Liaison Committee was quite something to behold, faced with thirty or so of Parliament’s leading experts Blair, on his own, would range with apparent ease across a wide and diverse range of policy areas. With the Parliamentary vote on military action in Iraq, Blair also established the convention whereby Parliament would be allowed to vote on British participation in hostilities abroad. Whatever the failings of Blair’s case for war in Iraq, this precedent almost certainly prevented British involvement in US-led military action in Syria earlier this year.

Another criticism of Blair was that his apparent neglect of Parliament set a bad example to other MPs, particularly in his own party. Critics of Parliament will often point to the photographs of an empty Commons chamber as evidence that our representatives are not working on our behalf. Aside from the television coverage, there are now a number of websites which allow us to track the activities of our MPs in Parliament, including Public Whip, and They Work For You. These sites arguably provide a useful service which allow voters to check that MPs are busy working on their behalf. However, they are not universally popular with MPs. In part this is because they are based on the assumption that MPs who are not speaking or voting in the chamber of the House of Commons are not working, when in fact they may be holding the government to account in a range of other settings, as is exemplified by the Prime Minister’s appearance before the Liaison Committee. MPs may be scrutinising the government through membership of a select committee, seeking to press our views on those in power by writing letters to Ministers or other public bodies, or as Tyrie observes by buttonholing Ministers in the tea rooms of Westminster. If they are government Ministers (including the Prime Minister) they may, indeed should, be developing policy in their department. Moreover, in many of these things the potential for MPs to have a significant impact on national policy or its impact on their constituency may be significantly greater than if they were speaking, or voting, in Parliament. The problem with many of these things is that they are much harder to demonstrate and measure. But we should perhaps bear them in mind and don’t assume that if MPs are not trooping through the division lobby pursued by the Party Whip they must be quaffing champagne on the terrace, the chances are they’re doing something very important, arguably with greater impact somewhere else.